Neal Dempsey, My Life Story

CHAPTER ONE

The Early Years

My parents were married in Aldershot in 1931. Ten months later my brother Patrick was born. My father was born in Fermoy in Southern Ireland, and came from a large family. His mother had not seen any of her Grandchildren as most of his brothers and Sister who were now married, had immigrated to America and had not been back to Ireland. My Grandfather had served in the army during the First World War. Before and after his military service he had worked on the Railway as a Platelayer. His foot had been crushed when a rail had been dropped on it and had subsequently been invalided out of the Railway with a pension. He then started up a small market garden with a donkey and cart to take his produce to the market to sell. My Grandmother used the donkey and cart also to take her into the town to do her shopping or go to mass. She was a devout Catholic. My Grandmother was desperate to see at least one of her Grandchildren. To oblige, my mother started to take an annual holiday with her to enable her to enjoy 'Paddy'. As my father was in the Brigade of Guards she was able to obtain an army travel voucher to get there.

My parents were married in Aldershot in 1931. Ten months later my brother Patrick was born. My father was born in Fermoy in Southern Ireland, and came from a large family. His mother had not seen any of her Grandchildren as most of his brothers and Sister who were now married, had immigrated to America and had not been back to Ireland. My Grandfather had served in the army during the First World War. Before and after his military service he had worked on the Railway as a Platelayer. His foot had been crushed when a rail had been dropped on it and had subsequently been invalided out of the Railway with a pension. He then started up a small market garden with a donkey and cart to take his produce to the market to sell. My Grandmother used the donkey and cart also to take her into the town to do her shopping or go to mass. She was a devout Catholic. My Grandmother was desperate to see at least one of her Grandchildren. To oblige, my mother started to take an annual holiday with her to enable her to enjoy 'Paddy'. As my father was in the Brigade of Guards she was able to obtain an army travel voucher to get there.

My father, Cornelius (Con') John DEMPSEY was serving in the 1st Battalion of the Irish Guards. My mother, Lucy Edna (Powis) was born on 1st March 1911 in Lancashire, but spent her formative years in Yorkshire where her father (Grandfather- Charles Powis) was a coalface miner. She had been a Christian of no particular persuasion and was not yet a Roman Catholic. In Southern Ireland at that time, there were bitter divisions between the English and Irish cultures resulting in the bloodshed and experiences visited upon the Irish by Winston Churchill's 'Black and Tans' in the 1920's were still fresh in the memory of the Irish people. The conclusion had been the division of the Country into what we now know as Ulster and Eire. They resented very much the presence of my mother and made several public demonstrations of their feelings, even to painting slogans across the road "English protestant go home!" and other less repeatable expressions. The irony is that most of the income of the older men of the town (Including my grandfather) came from English army pensions, and the recruiting officer for the Irish Guards, the fifth most senior regiment in the British army, was the Parish Priest.

My father, Cornelius (Con') John DEMPSEY was serving in the 1st Battalion of the Irish Guards. My mother, Lucy Edna (Powis) was born on 1st March 1911 in Lancashire, but spent her formative years in Yorkshire where her father (Grandfather- Charles Powis) was a coalface miner. She had been a Christian of no particular persuasion and was not yet a Roman Catholic. In Southern Ireland at that time, there were bitter divisions between the English and Irish cultures resulting in the bloodshed and experiences visited upon the Irish by Winston Churchill's 'Black and Tans' in the 1920's were still fresh in the memory of the Irish people. The conclusion had been the division of the Country into what we now know as Ulster and Eire. They resented very much the presence of my mother and made several public demonstrations of their feelings, even to painting slogans across the road "English protestant go home!" and other less repeatable expressions. The irony is that most of the income of the older men of the town (Including my grandfather) came from English army pensions, and the recruiting officer for the Irish Guards, the fifth most senior regiment in the British army, was the Parish Priest.

On the second of my mother's visits in 1934, I was born on the 15th June in the home of my paternal grandparents in a cottage known as 'The Grange' in Fermoy, in the County of Cork, Eire. I was afflicted with a harelip and cleft palate and no soft palate. I was unable to suckle and in those days such an affliction could be and often was fatal. Southern Ireland was and still is a very staunch Roman Catholic Country, therefore my grandmother baptised me immediately, taking me to the town church the next day Sunday17th June, and I was baptised again by the priest. Although I was a good healthy weight at birth, I began to lose weight causing great distress to my mother. My disfigurement would be considered as a punishment from God in the minds of the superstitious and cowardly hypocrites in the town. Ironically this attitude would be exactly in keeping with the old Jewish Biblical beliefs, which they (The townspeople) would have had no knowledge of. The only difference being that the Jews believed the afflicted (Myself) would have been the one that had lost favour with God, not my mother. My mother informs me that she was unable to feed me, so within a few days of my being born she went to the hospital in Fermoy and there saw the Geriatrician, he examined me and told my mother to bring me back in 12 months and they would try to operate. My mother said that at the present rate I would be dead long before then. The doctor just nodded and showed her the door.

On the second of my mother's visits in 1934, I was born on the 15th June in the home of my paternal grandparents in a cottage known as 'The Grange' in Fermoy, in the County of Cork, Eire. I was afflicted with a harelip and cleft palate and no soft palate. I was unable to suckle and in those days such an affliction could be and often was fatal. Southern Ireland was and still is a very staunch Roman Catholic Country, therefore my grandmother baptised me immediately, taking me to the town church the next day Sunday17th June, and I was baptised again by the priest. Although I was a good healthy weight at birth, I began to lose weight causing great distress to my mother. My disfigurement would be considered as a punishment from God in the minds of the superstitious and cowardly hypocrites in the town. Ironically this attitude would be exactly in keeping with the old Jewish Biblical beliefs, which they (The townspeople) would have had no knowledge of. The only difference being that the Jews believed the afflicted (Myself) would have been the one that had lost favour with God, not my mother. My mother informs me that she was unable to feed me, so within a few days of my being born she went to the hospital in Fermoy and there saw the Geriatrician, he examined me and told my mother to bring me back in 12 months and they would try to operate. My mother said that at the present rate I would be dead long before then. The doctor just nodded and showed her the door.

As soon as my mother was well and able enough, she came back to our home in London, and took me to "Tite Street" children's hospital in Chelsea, where she presented me to Mr Jennings-Marshall, the specialist Paediatrician. Despite my mothers' obvious fears and worry over my survival let alone well-being. Mr Jennings-Marshall was able to comfort and reassure her that all would be well. He took me into the hospital and undertook the first of what was to be a very lengthy series of operations to remodel my face. He brought the two edges of the gum margin together, affected a partial repair to the palate and a partial repair of the lip; sufficient to enable me to take food and thus improve and gain weight. Unfortunately although it improved my ability in time to be able to attempt to talk, conversation was extremely difficult and depended entirely on translation by my brother Paddy. Pad' apparently had no difficulty understanding every utterance I made, and for me became a vital link for a large number of years and at times in the most perverse of difficulties.

My earliest recollections were as a little boy in the late 1930's, probably aged 4 years old. We lived then in a flat, No 13 Q Block, Peabody Avenue, Victoria, London S.W.1. I can remember quite vividly playing on a carpet in front of the sideboard. Pad' and I had been given a bus conductors set comprising a hat, a clip board to hold tickets complete with a whole range of cardboard tickets, bag to hang over one shoulder for the money and a sling over the other shoulder to hold a ticket punch. My uncles and aunt, 'Brothers and sister of my father', were under strict instructions not to throw bus tickets away, but to add them to our collection. Anyone who stepped on the carpet was of course on our bus and had to pay the fare. I am certain I was robbed of vast sums of Ha'pennies and Farthings I had tried to extort in bus fares. Pennies and Ha'pennies were very valuable to Pad and myself at that time, because on Saturday morning we were taken to 'Nellie Dunn's' a sweet shop and general store at the end of the 'Avenue'. Nellie Dunn used to give a very good ration of Jelly Babies, and Dolly Mixtures to me at 1/4d a quarter. So for 1/2d each, Pad and I had sufficient sweets to last us until the next Saturday. (This largesse was apparently too much for Adolph Hitler because in 1940 he sent a squadron of Bombers to destroy Nellie Dunn's shop.) I can remember my father standing over me. He looked very, very big and tall. Strangely I have little or no recall of ever seeing him eye to eye. I am sure he must have picked me up and made a fuss of me at some time, but I cannot remember a single occasion when it happened. Whenever he spoke to me I can still see him waiting for Pad' to tell him what I had said in reply. Strangely at the time, that seemed right and proper. Now it upsets me to remember it.

My earliest recollections were as a little boy in the late 1930's, probably aged 4 years old. We lived then in a flat, No 13 Q Block, Peabody Avenue, Victoria, London S.W.1. I can remember quite vividly playing on a carpet in front of the sideboard. Pad' and I had been given a bus conductors set comprising a hat, a clip board to hold tickets complete with a whole range of cardboard tickets, bag to hang over one shoulder for the money and a sling over the other shoulder to hold a ticket punch. My uncles and aunt, 'Brothers and sister of my father', were under strict instructions not to throw bus tickets away, but to add them to our collection. Anyone who stepped on the carpet was of course on our bus and had to pay the fare. I am certain I was robbed of vast sums of Ha'pennies and Farthings I had tried to extort in bus fares. Pennies and Ha'pennies were very valuable to Pad and myself at that time, because on Saturday morning we were taken to 'Nellie Dunn's' a sweet shop and general store at the end of the 'Avenue'. Nellie Dunn used to give a very good ration of Jelly Babies, and Dolly Mixtures to me at 1/4d a quarter. So for 1/2d each, Pad and I had sufficient sweets to last us until the next Saturday. (This largesse was apparently too much for Adolph Hitler because in 1940 he sent a squadron of Bombers to destroy Nellie Dunn's shop.) I can remember my father standing over me. He looked very, very big and tall. Strangely I have little or no recall of ever seeing him eye to eye. I am sure he must have picked me up and made a fuss of me at some time, but I cannot remember a single occasion when it happened. Whenever he spoke to me I can still see him waiting for Pad' to tell him what I had said in reply. Strangely at the time, that seemed right and proper. Now it upsets me to remember it.

The Milkman used to go along the Avenue with his horse and cart ladling out the milk from a large milk churn on the cart into the people's jugs. The other traders had horses and carts except the Coalman who had a lorry, and our most daring trick was to try to hang on to the tail bar of this lorry as it sped up the Avenue. The lorry had to stop at the top entrance and wait for the porter to get the gate open to exit the estate, where we let go or fell off. The Avenue ran alongside the engine sheds for the trains for Victoria Railway Station. There were always big long distance trains and smaller Shunter trains moving about, ever a tremendous attraction for small boys. There was also a giant turntable where they could turn the engines around, or move them onto a different set of lines. Pad and I would sometimes get through a hole in the fence to go and watch the trains, until we were chased off. We must have been a nightmare for the Railway staff.

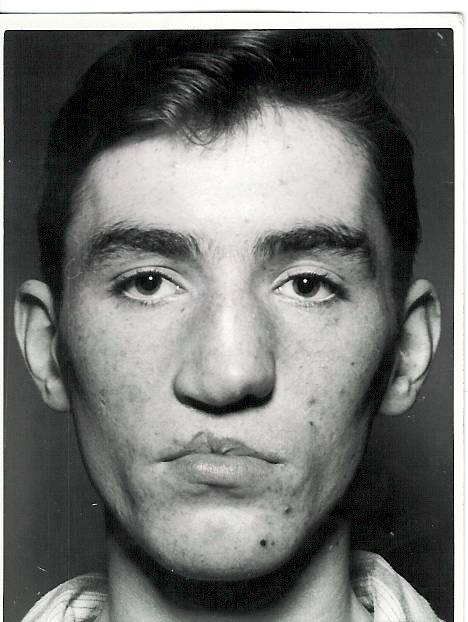

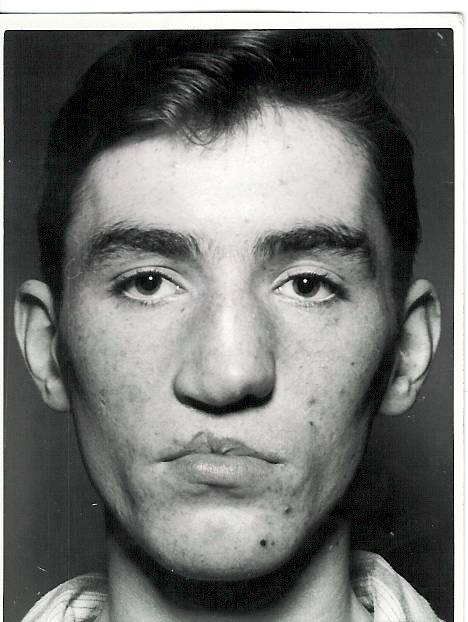

In all our adventures, and there were many. I was always blamed as the ringleader. In fact that was not true, I was desperate for friends, my only true friend was Pad', but I was taken along sometimes by other boys just so I would get the blame. I was the but of all jokes, not that I understood half of them. The biggest hurt was when I was called "Squashed tomato face" on account of the fact that my nose was so disfigured and flattened. Even in those tender years honour had to be satisfied, and if I couldn't get away from the tormentors a fight always ensued. We were not always victorious, but the other children knew we weren't a walk over. I think my mother was hurt more than I was in those years, there was a lot of sympathy from other mothers in the Avenue as well, but I wasn't aware of it at the time.

Paddy went at first to a Convent nursery school run by the Sisters of Charity by Westminster Cathedral. They ran a very strict regime, and Fish on Friday was a compulsory dish, everybody had to endure, there were no excuses. Unfortunately Paddy was allergic to Fish and was inevitably violently sick. The Nuns charity didn't seem to extend to little boys who were allergic to Fish, and so he was often punished either for not eating it or being sick after he had eaten it, a plea from my mother made no difference. My father eventually marched into the Convent and explained in a language even a brain dead guardsman would have no difficulty in understanding exactly where the Nuns could put their fish. Pad was duly removed from the school and placed in a school in Claverton Street underneath the Catholic Church there. Unfortunately he didn't settle, he became solitary and introvert, would not mix or join in any of the activities and began to alarm the teachers. He could well have been the same at the convent, but no one deemed it necessary to inform my mother if it was so. My mother was however called in to the nursery in Claverton Street. She seemed to think that he was missing me because he was perfectly all right at home, so despite the fact that I was under age, I was accepted into the school. As soon as I walked through the doors, Pad ran over and immediately began to take me around and show me all the features of this child's paradise. He never looked back and my education had begun. My coat peg was at the foot of the stairs at the entrance to the schoolroom and had a picture of a hand bell over it, a feature I will remember all my life.

The church and the nursery received a direct hit from a German bomb during the war. When hostilities ceased a prefabricated church was built in the shell of the old nursery and when we returned in 1945, my coat peg was still there, it had survived the might of the Luftwaffe.

The happy times were when my mother took us over Chelsea Bridge to Battersea Park. This was a wide-open haven of grass meadows, a boating lake (Which we never went on) there were ducks to feed and also a large enclosure with Deer in. Pad and I used to run wild in the park kicking a ball around. When we came out of the park to cross back over the bridge to go home, there was a man with an Ice Cream Sellers tricycle, who also sold Nougat, Monkey nuts and small round ice creams. The Nuts were still in the shells and there was always a litter of nutshells all around him. Incidentally when the present Chelsea Bridge was first opened to the public and transport; my mother took us to the official opening and we became one of the first to walk across it with Michael being pushed in his pram. (Sadly Battersea Park as I remember it was destroyed in 1951 during the Festival of Britain to make it into a theme park which it still is.)

My big problem was still a communication one. I still needed my interpreter. My impediment got worse if I became excited or distressed. I was taken for speech therapy on a regular basis, and it was obviously an improvement but not as much as everybody hoped. This proved to be to everyone's benefit and made life a bit easier for my mother.

My picture as taken in 1950 before any operations at Oxford showing the squashed tomato face and top lip repair originally carried out at Tite Street.

Return to index

|

Copyright © 2005, The Dempsey Family

|

| Please send your comments to ccd@ |

classicbookshelf |

|

com |

My parents were married in Aldershot in 1931. Ten months later my brother Patrick was born. My father was born in Fermoy in Southern Ireland, and came from a large family. His mother had not seen any of her Grandchildren as most of his brothers and Sister who were now married, had immigrated to America and had not been back to Ireland. My Grandfather had served in the army during the First World War. Before and after his military service he had worked on the Railway as a Platelayer. His foot had been crushed when a rail had been dropped on it and had subsequently been invalided out of the Railway with a pension. He then started up a small market garden with a donkey and cart to take his produce to the market to sell. My Grandmother used the donkey and cart also to take her into the town to do her shopping or go to mass. She was a devout Catholic. My Grandmother was desperate to see at least one of her Grandchildren. To oblige, my mother started to take an annual holiday with her to enable her to enjoy 'Paddy'. As my father was in the Brigade of Guards she was able to obtain an army travel voucher to get there.

My parents were married in Aldershot in 1931. Ten months later my brother Patrick was born. My father was born in Fermoy in Southern Ireland, and came from a large family. His mother had not seen any of her Grandchildren as most of his brothers and Sister who were now married, had immigrated to America and had not been back to Ireland. My Grandfather had served in the army during the First World War. Before and after his military service he had worked on the Railway as a Platelayer. His foot had been crushed when a rail had been dropped on it and had subsequently been invalided out of the Railway with a pension. He then started up a small market garden with a donkey and cart to take his produce to the market to sell. My Grandmother used the donkey and cart also to take her into the town to do her shopping or go to mass. She was a devout Catholic. My Grandmother was desperate to see at least one of her Grandchildren. To oblige, my mother started to take an annual holiday with her to enable her to enjoy 'Paddy'. As my father was in the Brigade of Guards she was able to obtain an army travel voucher to get there. My father, Cornelius (Con') John DEMPSEY was serving in the 1st Battalion of the Irish Guards. My mother, Lucy Edna (Powis) was born on 1st March 1911 in Lancashire, but spent her formative years in Yorkshire where her father (Grandfather- Charles Powis) was a coalface miner. She had been a Christian of no particular persuasion and was not yet a Roman Catholic. In Southern Ireland at that time, there were bitter divisions between the English and Irish cultures resulting in the bloodshed and experiences visited upon the Irish by Winston Churchill's 'Black and Tans' in the 1920's were still fresh in the memory of the Irish people. The conclusion had been the division of the Country into what we now know as Ulster and Eire. They resented very much the presence of my mother and made several public demonstrations of their feelings, even to painting slogans across the road "English protestant go home!" and other less repeatable expressions. The irony is that most of the income of the older men of the town (Including my grandfather) came from English army pensions, and the recruiting officer for the Irish Guards, the fifth most senior regiment in the British army, was the Parish Priest.

My father, Cornelius (Con') John DEMPSEY was serving in the 1st Battalion of the Irish Guards. My mother, Lucy Edna (Powis) was born on 1st March 1911 in Lancashire, but spent her formative years in Yorkshire where her father (Grandfather- Charles Powis) was a coalface miner. She had been a Christian of no particular persuasion and was not yet a Roman Catholic. In Southern Ireland at that time, there were bitter divisions between the English and Irish cultures resulting in the bloodshed and experiences visited upon the Irish by Winston Churchill's 'Black and Tans' in the 1920's were still fresh in the memory of the Irish people. The conclusion had been the division of the Country into what we now know as Ulster and Eire. They resented very much the presence of my mother and made several public demonstrations of their feelings, even to painting slogans across the road "English protestant go home!" and other less repeatable expressions. The irony is that most of the income of the older men of the town (Including my grandfather) came from English army pensions, and the recruiting officer for the Irish Guards, the fifth most senior regiment in the British army, was the Parish Priest.  On the second of my mother's visits in 1934, I was born on the 15th June in the home of my paternal grandparents in a cottage known as 'The Grange' in Fermoy, in the County of Cork, Eire. I was afflicted with a harelip and cleft palate and no soft palate. I was unable to suckle and in those days such an affliction could be and often was fatal. Southern Ireland was and still is a very staunch Roman Catholic Country, therefore my grandmother baptised me immediately, taking me to the town church the next day Sunday17th June, and I was baptised again by the priest. Although I was a good healthy weight at birth, I began to lose weight causing great distress to my mother. My disfigurement would be considered as a punishment from God in the minds of the superstitious and cowardly hypocrites in the town. Ironically this attitude would be exactly in keeping with the old Jewish Biblical beliefs, which they (The townspeople) would have had no knowledge of. The only difference being that the Jews believed the afflicted (Myself) would have been the one that had lost favour with God, not my mother. My mother informs me that she was unable to feed me, so within a few days of my being born she went to the hospital in Fermoy and there saw the Geriatrician, he examined me and told my mother to bring me back in 12 months and they would try to operate. My mother said that at the present rate I would be dead long before then. The doctor just nodded and showed her the door.

On the second of my mother's visits in 1934, I was born on the 15th June in the home of my paternal grandparents in a cottage known as 'The Grange' in Fermoy, in the County of Cork, Eire. I was afflicted with a harelip and cleft palate and no soft palate. I was unable to suckle and in those days such an affliction could be and often was fatal. Southern Ireland was and still is a very staunch Roman Catholic Country, therefore my grandmother baptised me immediately, taking me to the town church the next day Sunday17th June, and I was baptised again by the priest. Although I was a good healthy weight at birth, I began to lose weight causing great distress to my mother. My disfigurement would be considered as a punishment from God in the minds of the superstitious and cowardly hypocrites in the town. Ironically this attitude would be exactly in keeping with the old Jewish Biblical beliefs, which they (The townspeople) would have had no knowledge of. The only difference being that the Jews believed the afflicted (Myself) would have been the one that had lost favour with God, not my mother. My mother informs me that she was unable to feed me, so within a few days of my being born she went to the hospital in Fermoy and there saw the Geriatrician, he examined me and told my mother to bring me back in 12 months and they would try to operate. My mother said that at the present rate I would be dead long before then. The doctor just nodded and showed her the door.  My earliest recollections were as a little boy in the late 1930's, probably aged 4 years old. We lived then in a flat, No 13 Q Block, Peabody Avenue, Victoria, London S.W.1. I can remember quite vividly playing on a carpet in front of the sideboard. Pad' and I had been given a bus conductors set comprising a hat, a clip board to hold tickets complete with a whole range of cardboard tickets, bag to hang over one shoulder for the money and a sling over the other shoulder to hold a ticket punch. My uncles and aunt, 'Brothers and sister of my father', were under strict instructions not to throw bus tickets away, but to add them to our collection. Anyone who stepped on the carpet was of course on our bus and had to pay the fare. I am certain I was robbed of vast sums of Ha'pennies and Farthings I had tried to extort in bus fares. Pennies and Ha'pennies were very valuable to Pad and myself at that time, because on Saturday morning we were taken to 'Nellie Dunn's' a sweet shop and general store at the end of the 'Avenue'. Nellie Dunn used to give a very good ration of Jelly Babies, and Dolly Mixtures to me at 1/4d a quarter. So for 1/2d each, Pad and I had sufficient sweets to last us until the next Saturday. (This largesse was apparently too much for Adolph Hitler because in 1940 he sent a squadron of Bombers to destroy Nellie Dunn's shop.) I can remember my father standing over me. He looked very, very big and tall. Strangely I have little or no recall of ever seeing him eye to eye. I am sure he must have picked me up and made a fuss of me at some time, but I cannot remember a single occasion when it happened. Whenever he spoke to me I can still see him waiting for Pad' to tell him what I had said in reply. Strangely at the time, that seemed right and proper. Now it upsets me to remember it.

My earliest recollections were as a little boy in the late 1930's, probably aged 4 years old. We lived then in a flat, No 13 Q Block, Peabody Avenue, Victoria, London S.W.1. I can remember quite vividly playing on a carpet in front of the sideboard. Pad' and I had been given a bus conductors set comprising a hat, a clip board to hold tickets complete with a whole range of cardboard tickets, bag to hang over one shoulder for the money and a sling over the other shoulder to hold a ticket punch. My uncles and aunt, 'Brothers and sister of my father', were under strict instructions not to throw bus tickets away, but to add them to our collection. Anyone who stepped on the carpet was of course on our bus and had to pay the fare. I am certain I was robbed of vast sums of Ha'pennies and Farthings I had tried to extort in bus fares. Pennies and Ha'pennies were very valuable to Pad and myself at that time, because on Saturday morning we were taken to 'Nellie Dunn's' a sweet shop and general store at the end of the 'Avenue'. Nellie Dunn used to give a very good ration of Jelly Babies, and Dolly Mixtures to me at 1/4d a quarter. So for 1/2d each, Pad and I had sufficient sweets to last us until the next Saturday. (This largesse was apparently too much for Adolph Hitler because in 1940 he sent a squadron of Bombers to destroy Nellie Dunn's shop.) I can remember my father standing over me. He looked very, very big and tall. Strangely I have little or no recall of ever seeing him eye to eye. I am sure he must have picked me up and made a fuss of me at some time, but I cannot remember a single occasion when it happened. Whenever he spoke to me I can still see him waiting for Pad' to tell him what I had said in reply. Strangely at the time, that seemed right and proper. Now it upsets me to remember it.