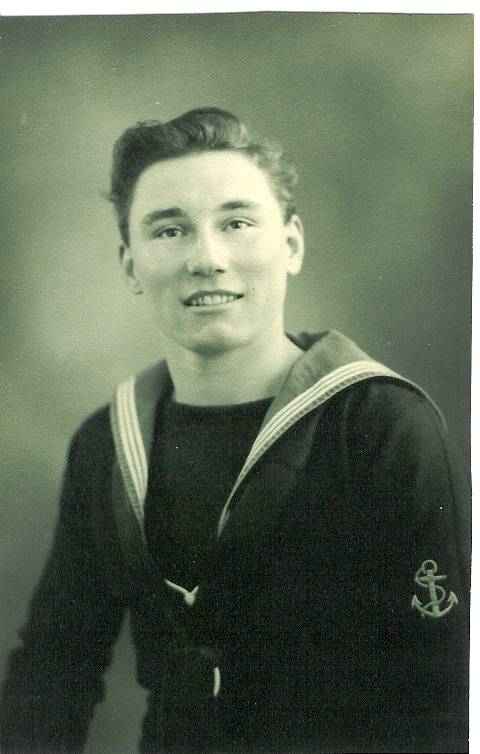

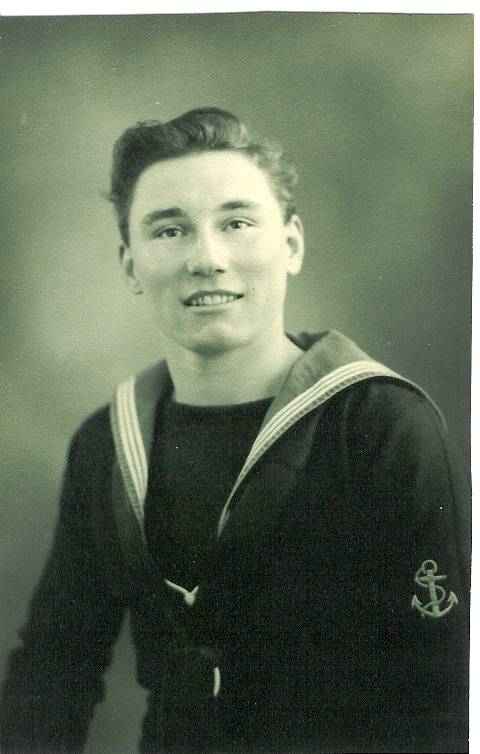

Neal Dempsey, My Life Story

CHAPTER FIVE

Leaving Home

My call up came eventually informing me that I was to report to Victoria Barracks in Portsmouth on 15th May 1952 just 1 month before my 18th Birthday. I had a Railway Warrant sent to me, which I cashed at the ticket Office at Waterloo Station. I was given instructions to go to Portsmouth Town Station and there report to the Naval Patrol who would be waiting at the Station. I felt a mixture of excitement and concern as to whether I really had done the right thing. Victoria Barracks was an imposing pile of old Victorian style architecture quite close to South Parade in Portsmouth overlooking the Solent. It had been condemned years before as being unfit for occupation, but because of the recently ended World War 2, the ongoing Korean War, the Malayan Crisis (Unofficial anti communist war) the Jewish terrorist campaign in Palestine and EOKA crisis in Cyprus; it was still very much in use. The fun fair was just a few hundred yards away and my earliest recall of that was the incessant playing of the top tune of the day "Oh wheel of Fortune." I was lined up with a group of other young men of my own age group, and a Gunnery Petty Officer who was to be our class instructor for the next six weeks of basic training introduced us to the barrack life.

He lined us up roughly according to size and after picking up our cases; we were 'Marched!' up to our dormitory, which was on the first floor of one of the blocks. The bunks were doubled up, one above the other and in the passage between each pair of bunks was a metal locker, half each for the top and bottom bunk. No wardrobes or hanging space. Everything had to be folded and put away. There was a row of coat hooks for our raincoats we were to be issued with later. After being introduced to the do's and don'ts concerning our living space etc; and what our duties were in that regard, we were taken on the grand tour of the Barracks. We were then taken to the pay office and given 10/-. Our first payday! I felt like a king so rich, I had hardly got used to the idea of such wealth when we were marched around to the "Slops" that is Naval Stores where we were each given a small brown suitcase into which was put our toothbrush, toothpaste, shaving kit, shoe cleaning equipment (Black) two small towels, Two large towels, socks, Housewife (sewing kit) soap, including washing soap known as 'Pusser's Hard'. A bevy of smiling WRENS who made us feel very grown up dropped all of these goodies into our cases. The big let down came at the far end of the row when a not so smiley Chief Petty Officer demanded 9/6d leaving me with a mere 6d to last me until the next payday.

Having been shown the dining room and learning the routine, we were told that we would not be allowed to go out of the Barracks for fourteen days and then subject only to having been successful in our behaviour and presentation. We were allowed to find our bearings that evening but the next morning the Reveille roused us at 7.a.m. and the first day's rush around began. Our kind smiley Petty Officer was there with a vengeance screaming and shouting and I certainly wasn't going to get an early morning cup of tea. I moved and made every effort not to call attention to myself, although everything was a bit of a blur. The food was plentiful including a full cooked breakfast and buckets of tea. We very quickly learned to look after our own enamel mug and personal cutlery (Eating irons). Everyone seemed to eat at the double and if one didn't keep up one soon got left behind. Afterwards we were lined up by our beds and shown how they were to be left from that moment on, a passing threat no one seemed to miss. The instructors seemed to have a very clear way of making themselves understood. The language, swearing and blasphemy were all around and if anyone showed any dislike it was showered on them even more forcefully. The whole routine was a total culture shock. After ensuring the mess (The word dormitory was now no longer used, we were told girls at 'Roedean' slept in dormitories) was spotless and fit for the Officer of the day to inspect without causing him to be too traumatised. He was very sensitive about such things we were informed. The dry wit took a little time to be got used to.

We were fallen in on the small parade ground outside our block. Here we were told we were not going to be allowed to go on to the big parade ground with the real sailors until we began to look a bit like them, because the Petty Officer didn't want to give the Gunnery Officer a Heart Attack, as he explained he was very fond of the man and his health could be made frail by our shambling about like a lot of delinquents, which we were then informed was contrary to the articles of war and Naval Discipline and was a hanging offence! More dry humour. Having explained exactly where we fitted in the ranks of the Royal Navy, and within the social structure of society in general, then we were taken to be kitted out in our uniforms. This was not exactly intended to be a moral boosting exercise apparently, but secretly I found it hilarious. We were all described as miscellaneous men, that is Writers (Scribes), Stores assistants (Jack Dusties) a couple of Shipwright Apprentices (Chippies) and Sick Berth Attendants (Doc's). The rank and file of the Royal Navy is nothing if not perverse in all things. Doctors or Surgeons were referred to as 'Quacks' and their assistants as 'Doc'. We were to wear 'Fore and Aft' rig, that is a suit and tie with a peaked cap. We were taken back to the 'Slops' and given two uniforms, two caps shirts underpants, pyjamas sheets for our beds a blanket, Hammock, Hammock mattress, Clues and Lashings, boots (Two pairs, but only one pair to have studs in), everything in fact that we needed. From now on we would have to take our civilian clothes home, we would not be allowed to wear them again while we were in the barracks they were exclusively for use 'Up the line' that is to say at home. Then to the kit marking room to mark all of our black and dark clothes with white paint and all of our white clothes, towels, sheets etc., with black paint. While all of this activity was going on we were being regaled with a host of information we had to remember by heart. We were told at this stage that we had one week to make up our minds whether we stayed, but if we didn't like it after one week we were in for Seven Years at least, unless they decided to throw us out. By the end of the day I was dizzy. I learned that one chap left the first day, two more left after a couple of days, another had been found committing some crime or other and he was sent packing immediately. We ended up with a class of sixteen men out of twenty. One more chap was found to be totally unsuitable and released after five weeks, he left in tears because he really wanted to stay, but with hindsight I think they were absolutely right to send him home, he would have suffered terribly had he stayed.

For the first month I was in a daze, I tried hard and did quite well except that I was a loner and did not make any friends readily. I didn't even know who would be going on with me as Sick Berth Attendants. Despite this I really did enjoy the training, it was so different to anything I had ever known before. A course at the damage control school; a day at H.M.S Phoenix, where we did our fire-fighting course. We were taken down to the harbour on one occasion and told we were shipwrecked and taken by small boat to H.M.S. Forth, a huge Submarine Depot Ship. They were doing an exercise on rescue at sea. They had to victual us and look after us for 24 hours. We were messed in a giant store area and I slept in a hammock for the first time. We all enjoyed that very much. We were taut every thing we needed to know about how to look after ourselves to washing, ironing, sewing, even to being shown around the galley. We had to do duties every fourth night, which almost always comprised walking around the inside of the perimeter wall for four hours particularly behind the WRENS quarters. I was regaled by many suspect experts on all of the lurid goings on in that barrack block. It always puzzled me as to how these men knew because I would stake my life they had never been inside that hallowed ground.

After two weeks in the barracks we were allowed out in the evening if we were not on duty, to be back by midnight. I went round to H.M.S. Vernon to visit Pad' on my first outing. Pad was a Leading Seaman stationed there at that time as part of the guard. When I got there He was on the main gate, I spoke to him for a few moments and as I didn't have any money I asked him if he would lend me a few shillings, but he said he didn't have any money either, so I came away just as broke. This was the last time I saw Pad for nearly a year, he didn't call on me or suggest a run ashore to go for a drink. I was a 'Nozzer' (New Recruit) and he was a leading hand, and he had his own mates. My runs ashore for the first three weeks comprised a walk along Southsea front and then back into barracks. I just didn't have any money, what little I got in pay mostly went on refreshment at stand easy in the morning in the NAAFI. I had made out an allotment to my Mother of half my pay, little realising how little I would have left and I didn't have the courage to go and change the allotment. However after two weeks we were paraded and issued with 300 duty free cigarettes for which we had to pay 5/-. They didn't have a Brand name but a blue line down the side of the cigarette and marked 'H.M. Ships only'. We received this issue every month. I soon learned that this was a currency. I didn't smoke and I found that people would buy these cigarettes from me for 1/- a packet so I could make a profit of 10/-. This was strictly illegal as it was thought of as smuggling, but no one paid a blind bit of notice except the Dockyard Police who only turned a blind eye if you sold the cigarettes to them. We also got 3d a day in lieu of a Rum ration after our 18th Birthday. Rum was not issued to new entrants. Below 18 years we were classified as 'U.A.' (Under age) and so not entitled.

After two weeks in the barracks we were allowed out in the evening if we were not on duty, to be back by midnight. I went round to H.M.S. Vernon to visit Pad' on my first outing. Pad was a Leading Seaman stationed there at that time as part of the guard. When I got there He was on the main gate, I spoke to him for a few moments and as I didn't have any money I asked him if he would lend me a few shillings, but he said he didn't have any money either, so I came away just as broke. This was the last time I saw Pad for nearly a year, he didn't call on me or suggest a run ashore to go for a drink. I was a 'Nozzer' (New Recruit) and he was a leading hand, and he had his own mates. My runs ashore for the first three weeks comprised a walk along Southsea front and then back into barracks. I just didn't have any money, what little I got in pay mostly went on refreshment at stand easy in the morning in the NAAFI. I had made out an allotment to my Mother of half my pay, little realising how little I would have left and I didn't have the courage to go and change the allotment. However after two weeks we were paraded and issued with 300 duty free cigarettes for which we had to pay 5/-. They didn't have a Brand name but a blue line down the side of the cigarette and marked 'H.M. Ships only'. We received this issue every month. I soon learned that this was a currency. I didn't smoke and I found that people would buy these cigarettes from me for 1/- a packet so I could make a profit of 10/-. This was strictly illegal as it was thought of as smuggling, but no one paid a blind bit of notice except the Dockyard Police who only turned a blind eye if you sold the cigarettes to them. We also got 3d a day in lieu of a Rum ration after our 18th Birthday. Rum was not issued to new entrants. Below 18 years we were classified as 'U.A.' (Under age) and so not entitled.

I was frequently amazed at the exploits some of the men seemed to get up to when they were ashore. How much of it was truth and how much was fantasy I'll never know. One or two of them would come into the mess late at night and pretend to be drunk and create a nuisance. That was not tolerated; if they got past the main gate they weren't drunk, because if they had been they would have spent the rest of the night in the cells.

There were one or two bullies in the class and they tended to pick on the weaker man and myself. At the end of one month after a particular incident on the parade ground, back in the mess they picked on the other chap who really could not march and couldn't control his rifle no matter how hard he tried, they started to punch and swear at him, I saw red and went for them. A fight ensued with me in the middle of it. I saw the 'P.O' come into the mess, turn around and walk out again. I think he just stood around outside smoking a cigarette and waiting. When it was over he came in again screaming and shouting that he was going to get us all flogged and to get the mess cleaned up sharp. 20 minutes later he had us all on the parade ground doubling around for half an hour until we were all completely exhausted. We were dismissed and told we would all be in front of the Captain in the morning. The next morning we all paraded waiting to be marched before the Captain, when we were asked who came out of the fight the best, I was nominated by the others as the one who sorted out the trouble makers and I was then promptly made Class Leader and told if there was any more trouble I would be held responsible. There was no more trouble and we passed out as we were expected to. I must say that although the discipline was harsh it was humane. There was no mindless bullying, everything was explained and the reasons for doing things in the way we were expected to do them.

The instructors were mostly retired men who had been recalled because of the Korean War, which was ongoing at that time. They had a wealth of knowledge and experience tinged with a strong sense of humour, which appealed to me. I have always had a very acute sense of humour despite everything. The instructor who struck me most forcibly was the Chief Petty Officer Gunner, who ran the parade ground. He came up to my shoulder with his cap on. He could not have been much over Five feet in height, but he had a voice like a foghorn, a vocabulary like an open drain and a wicked sense of humour. But for some perverse reason we all liked 'Obi-Diah' as he told us he was called. On the Friday lunchtime, at the end of our training, we were given a railway pass to go home for the weekend and be back Sunday night. This in the naval vernacular was known as a 'Friday While'. Before we were released to leave each of us was interviewed by our class instructor and given our individual assessment. I was told that up until the incident in which I had got involved in the fight in the mess deck two weeks previously, there had been serious debate over whether I would be retained or discharged at the end of the six weeks. I had been too quiet and uncommunicative, but after that incident I had begun to force issues that had been accepted by the rest of the recruits. This was a psychological and moral milestone for me. People accepted me as I was and treated me with a little more respect. I felt a terrific burden had been lifted from me. Moving away from a semi protective environment had been the right thing to do. I began to have a lot more confidence in myself.

Return to index

|

Copyright © 2005, The Dempsey Family

|

| Please send your comments to ccd@ |

classicbookshelf |

|

com |

After two weeks in the barracks we were allowed out in the evening if we were not on duty, to be back by midnight. I went round to H.M.S. Vernon to visit Pad' on my first outing. Pad was a Leading Seaman stationed there at that time as part of the guard. When I got there He was on the main gate, I spoke to him for a few moments and as I didn't have any money I asked him if he would lend me a few shillings, but he said he didn't have any money either, so I came away just as broke. This was the last time I saw Pad for nearly a year, he didn't call on me or suggest a run ashore to go for a drink. I was a 'Nozzer' (New Recruit) and he was a leading hand, and he had his own mates. My runs ashore for the first three weeks comprised a walk along Southsea front and then back into barracks. I just didn't have any money, what little I got in pay mostly went on refreshment at stand easy in the morning in the NAAFI. I had made out an allotment to my Mother of half my pay, little realising how little I would have left and I didn't have the courage to go and change the allotment. However after two weeks we were paraded and issued with 300 duty free cigarettes for which we had to pay 5/-. They didn't have a Brand name but a blue line down the side of the cigarette and marked 'H.M. Ships only'. We received this issue every month. I soon learned that this was a currency. I didn't smoke and I found that people would buy these cigarettes from me for 1/- a packet so I could make a profit of 10/-. This was strictly illegal as it was thought of as smuggling, but no one paid a blind bit of notice except the Dockyard Police who only turned a blind eye if you sold the cigarettes to them. We also got 3d a day in lieu of a Rum ration after our 18th Birthday. Rum was not issued to new entrants. Below 18 years we were classified as 'U.A.' (Under age) and so not entitled.

After two weeks in the barracks we were allowed out in the evening if we were not on duty, to be back by midnight. I went round to H.M.S. Vernon to visit Pad' on my first outing. Pad was a Leading Seaman stationed there at that time as part of the guard. When I got there He was on the main gate, I spoke to him for a few moments and as I didn't have any money I asked him if he would lend me a few shillings, but he said he didn't have any money either, so I came away just as broke. This was the last time I saw Pad for nearly a year, he didn't call on me or suggest a run ashore to go for a drink. I was a 'Nozzer' (New Recruit) and he was a leading hand, and he had his own mates. My runs ashore for the first three weeks comprised a walk along Southsea front and then back into barracks. I just didn't have any money, what little I got in pay mostly went on refreshment at stand easy in the morning in the NAAFI. I had made out an allotment to my Mother of half my pay, little realising how little I would have left and I didn't have the courage to go and change the allotment. However after two weeks we were paraded and issued with 300 duty free cigarettes for which we had to pay 5/-. They didn't have a Brand name but a blue line down the side of the cigarette and marked 'H.M. Ships only'. We received this issue every month. I soon learned that this was a currency. I didn't smoke and I found that people would buy these cigarettes from me for 1/- a packet so I could make a profit of 10/-. This was strictly illegal as it was thought of as smuggling, but no one paid a blind bit of notice except the Dockyard Police who only turned a blind eye if you sold the cigarettes to them. We also got 3d a day in lieu of a Rum ration after our 18th Birthday. Rum was not issued to new entrants. Below 18 years we were classified as 'U.A.' (Under age) and so not entitled.