Neal Dempsey, My Life Story

CHAPTER ELEVEN

H.M.S Palliser

I joined H.M.S Palliser on Monday 12th March 1958.

The ship was involved with the rest of the Arctic Squadron in the Cod War off Iceland. The Cod War was over a dispute with Iceland over the extent of its territorial waters. Previously a Country could claim territorial water rights up to 3 miles from its coastline. A short time before there had been other incidents by Iceland, which had resulted in these rights being extended to 4 miles out to sea. Now Iceland was trying to impose a 12 miles limit much to the fury of all European and Scandinavian Fishermen. There is a shelf below these waters off Iceland known as the Icelandic shelf, which is rich in fish. Iceland maintained that their national economy depended on fishing and deep-water fishermen from elsewhere were robbing them of their living. While the matter was being sorted out diplomatically at The Hague, Britain was operating havens within the 12-mile limits, with Iceland's' reluctant but tacit approval. There were two havens operating each 12 miles long by 8 miles deep to the Icelandic territorial waters. The Havens were open to anyone and each was patrolled by a British Warship to protect the Trawlers and their crews, and to ensure that they did not fish outside the limits within the 12-mile boundary. The Navy also provided Engineering and Medical support for those trawlers and that was where I came in, but unwittingly at that stage.

I had travelled up overnight from London, leaving Kings Cross at about ten p.m. and arriving in Edinburgh at 7.a.m. I was sleepy eyed, tired, hungry and feeling a bit of a wreck. I was lost for a moment and asked a porter where I could get the train for Rosyth. He pointed to a platform and said something in broad Scots, which I didn't understand. I later worked out that he was telling me to get the train to Inverkeithing; it was just as well I didn't understand him because I'd never heard of the place. It transpired that this was the station for Rosyth. It was a relatively short journey across the Forth Bridge. When I arrived there were a number of other Sailors on the train, which was reassuring. Several of them asked if I was on Draft and offered to help me with my kit, for which I was very grateful. They walked into the dockyard where I found the ship alongside the jetty a hive of activity already. The smell, noise and hustle and bustle of a working warship alongside is and was for me quite magic. I was deep down feeling very proud and excited to think that I was part of the scene. I was immediately recognised for what I was and I heard the bosuns' call for the Sick Bay Tiff' to come to the brow (Of the gangway) his relief had arrived and was waiting on the Jetty. I was just standing starry-eyed drinking in the atmosphere. Moments later he came running down the gangplank to shake my hand and already had hands organised to help me get my kit aboard. In moments I was in the Sick Bay with a giant mug of steaming tea in my hand.

The Sick Bay was on the main deck on the Port side a few feet along from the bulkhead door out onto the main outside deck. The room was about 14 feet long and 10 feet wide. There were two scuttles (Portholes) one in the main sick bay and the other in the bathroom/toilet/darkroom. This was an area 6 feet by 5 feet taken out of the whole. Between the bathroom and the forward bulkhead there were two cots, one over the other suspended on a centre pole at each end so that they could move freely with the ships motion at sea. Each one had sides, which could be clipped up or lowered like a babies cot. Against the inside bulkhead there was a desk and cupboards for equipment and medicines. The whole set up was fully comprehensive right down to an anaesthetics trolley, and a Portex X-ray machine. In emergency the Wardroom (Officers Mess) was converted into an Operating Theatre. There was a Doctor on board while we were in the Arctic, and he came into the sick bay very soon after I arrived, a Surgeon Lieutenant Campbell. A very senior member of the Campbell Clan he was proud to inform me, but gratefully he spoke in a very refined Oxbridge accent so I had no difficulty in understanding him.

There were 120 men in the Ships Company. The normal complement for a ship of this size would be 90 men, but it was considered to be a war complement. The Captain was a Lieutenant Commander, he was the junior Captain in the Squadron so we were in effect the junior ship and got the rough duties. I couldn't have cared less about that I just wanted to be a part of it. My next visit was to the Coxswain. A Chief Petty Officer, he was in effect the Master at Arms and ran the ship. I was messed right Aft in a small room that ran the width of the ship, we slept in Hummocks and there were 15 other men in the mess. One entered the mess through a vertical hatch and down a ladder. There was another smaller mess branching off it, with 8 men in. once we got to sea, the main deck bulkhead door was closed and we had to walk aft over the deck housing and drop through two vertical ladders to get to the mess because the main deck would mostly be awash in a heavy sea. In harbour there was just 8 feet freeboard between the sea and the main deck, often at sea there was nothing, which I was soon to find out for myself. This created obvious difficulties because all meals were eaten on the mess deck, which meant it had to be carried from the galley to the mess, so in inclement weather it had to be taken up one deck taken out through the weather door and along the upper deck around all the funnels and ventilator shafts for the engine room etc, then down two vertical ladders to the mess deck. If it was cold or raining, it was a perilous journey.

I had just one day to take over from my predecessor then I was on my own, we were due to sail on the Thursday after my arrival and I have never known a week fly by so quickly. I had been chasing around like a man possessed to find my way round the ship, and meeting everyone who mattered as well as doing the sick parades and treatments. I very soon made up my mind that even though men should report at 9.a.m if they were reporting sick, if someone came to me in the evening or afternoon because for one reason or another they couldn't come at the proper time, if they were genuine, I had no problem with that. I very soon winkled out the skivers and there were a couple, we reached an understanding! My predecessor took me ashore to Edinburgh that first night, when he visited all the low life with a few of the Ships Company. Quite frankly I was jolly glad to get back on board and not unhappy to see him off the next day and start to work myself into the crew. I worked hard going through the stock we carried. Every mess had its own first aid locker, which I checked and topped up a few. There were one or two store cupboards dotted around the ship in the most obscure places. I very soon found that this was a happy ship, the Officers expected work to be done but they were otherwise very easy going and no one seemed to abuse their position. By the time Thursday morning came I was 'Doc' and accepted openly by everyone. I had to see the First Lieutenant on the first day and was taken to see the Captain in his cabin and told what was expected of me. I just hoped I came up to expectations, but secretly I got out my books and started to refresh myself.

The Thursday morning we set sail, it was a cold bleak day. There was a damp mist saturating everything and we seemed to be the only boat moving. We left the dockyard and turned east to pass under the Forth Bridge and on out to the open sea, the side was manned until we passed the Flag Officers Residence, then the stand down was piped. The weather continued grey and the sea was completely flat until we came out of the Forth and turned north into the North Sea, now it began to get choppy. As we progressed the weather deteriorated and towards the evening we were heading into a force 8 gale. The weather continued to be unpleasant for the next three days. It is not at all unusual for some of the crewmembers to be seasick for the first couple of days, then they settle down and don't notice what the weather is like after that. The long-term problem I learnt with constant heavy weather was not seasickness but back pain. This is caused because one is constantly moving against the motion of the ship, mostly completely unconsciously and even in ones sleep. Most men had applied to stop shaving, but foolishly I didn't and I was to regret that later.

Once we were at sea, the doctor held his sick parade at 9.a.m and afterwards started giving me an instructional course on my duties, diagnosis and treatment. He made me question the patients and diagnose their conditions in front of him, he then expected me to prescribe treatment. Minor surgery he expected me to do under his supervision on the basis that if he was out of action for any reason, I would still have to carry on. I took all bloods and slides when they were necessary. I had to stain all the slides and diagnose. He argued that as we did more than the doctors we were often much better at it than a doctor. I only had the opportunity to use the X-ray unit once on that first trip, the result was very good and we were easily able to diagnose a fractured radius, and set it. I was very pleased with that, and the crew who were always interested in such matters were very impressed. I was very quickly respected and trusted. Seamen are a very hard lot to get their wholehearted trust.

We were going to patrol an area of the Northwest corner of Iceland and as we steamed up the west coast about 12 miles offshore, I saw Iceland for the first time. It looked bleak and I saw Mount Hecla which is an extinct volcano towering I don't know how far into the air. It reminded me of the Japanese pictures of Fujiyama with its snow-covered cap. Our haven had 70 trawlers fishing inside it with the Icelandic gunboat 'Odin' patrolling close to the 4 mile boundary ready to pounce on any trawler trespassing outside the Haven. The weather improved for three days over the Easter weekend and we were actually able to do some sunbathing on the upper deck, but it was not to last. On the Monday the weather deteriorated again and we began to get the injuries coming in from the trawlers. The skippers could deal with a lot of them, but some we were obliged to attend. Now for the first time I learnt about Life Raft Transfers. The Life Raft was a normal 10-man rubber raft, which was constructed by two circular tubes with a double skin bottom, again inflated. Inflated tubular arches crossed the raft with a skin between two opposing arches and openings between the other two for access and egress. There was a large hoop of steel the circumference of the raft with a canvas stretched across it on which the raft sat. this was held in place by four canvas straps which met over the top centre of the raft with a metal ring. The raft was lowered over the side by a crane hooked onto this ring and similarly when the raft returned it was hooked on and lifted out of the water hopefully complete with passenger. Little did I know that this was going to be my busiest form of transport for the next two years.

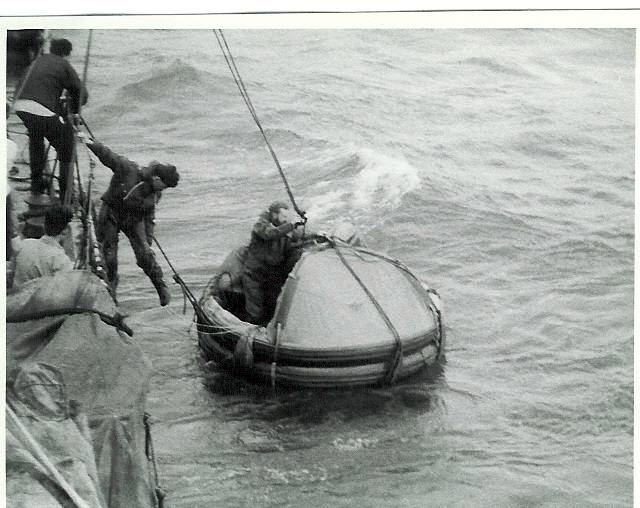

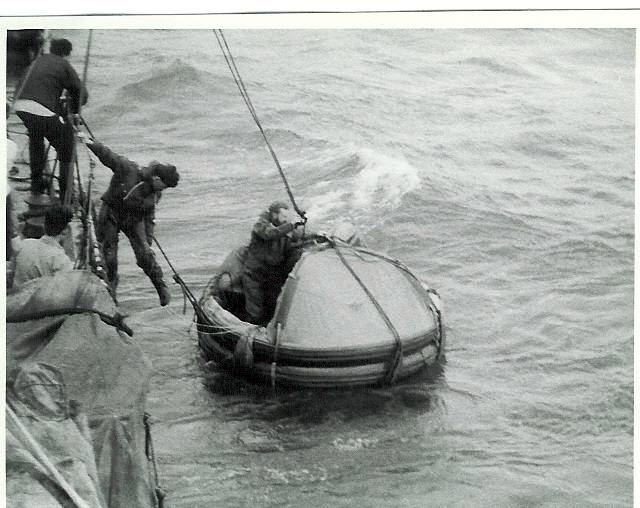

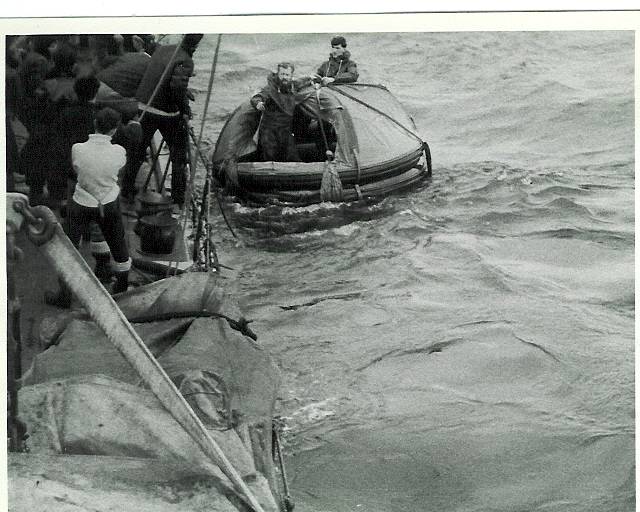

The picture shows the raft ready to go. The man on the deck is the First Lieutenant. The bearded man in the raft is the doctor and you can just see my face behind the doctor. In fine weather and the sea as you see it in the picture would be considered fine weather. There is a nylon line shot over the trawler, this is then attached to a thick line and the raft would be pulled across. It can only be done in fine weather because it means both ships remaining on station with the Frigate on the weather side. In inclement weather they couldn't do this because it would mean that the Frigate would be blown onto the trawler. In the picture you can see the line, which will be used to tow us across. Looking back I suppose this could be thought of as highly dangerous, but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

The picture shows the raft ready to go. The man on the deck is the First Lieutenant. The bearded man in the raft is the doctor and you can just see my face behind the doctor. In fine weather and the sea as you see it in the picture would be considered fine weather. There is a nylon line shot over the trawler, this is then attached to a thick line and the raft would be pulled across. It can only be done in fine weather because it means both ships remaining on station with the Frigate on the weather side. In inclement weather they couldn't do this because it would mean that the Frigate would be blown onto the trawler. In the picture you can see the line, which will be used to tow us across. Looking back I suppose this could be thought of as highly dangerous, but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

We wore what was referred to as an immersion suit to do the transfers in the raft. An immersion suit comprised a rubberised blouse with a hood. It had a tight rubber seal around the wrists of the sleeves and a rubber seal around the neck it also had a long rubber skirt, which came down to my knees. The trousers were of similar material with rubber boots like Wellingtons sealed to the bottoms. It was worn with strong bracers. The trousers also had a rubber skirt attached at the waist, which again came down to the knees. With both articles on the rubber skirts were rolled up together to give a watertight seal at the waist. It was a very comfortable piece of clothing to wear and very warm. It didn't keep ones face and hands warm though and that is why I should have grown a beard. Having to do a life raft transfer early in the day after having a shave, it felt as if a thousand knives were cutting into my face and my hands froze into claw shapes as I tried to manipulate the freezing wet ropes. Many, many times I had to get my hands thawed once I got onto trawlers before I could even think of doing anything for the patient.

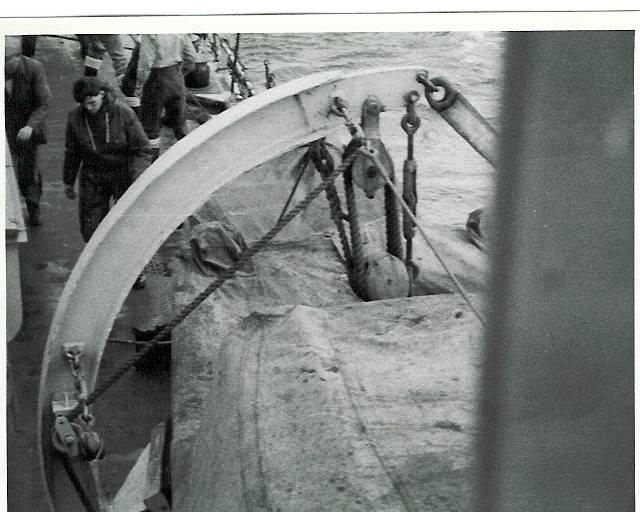

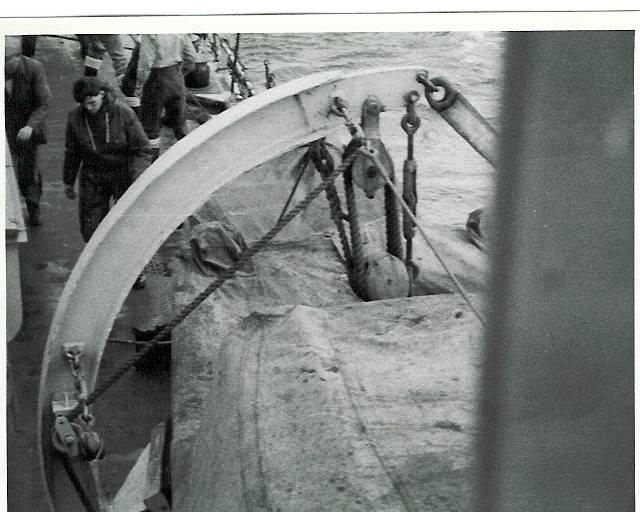

Getting aboard a trawler was never an easy task and one had to be a bit of an athlete and chancy with it on occasion. In this picture I am alongside the Hull Trawler 'Faraday' and as you can see the life raft is on the crest of a swell, now is the time to get on the trawler. The large board hanging from the side of the trawler, from what they call the gallows. This is one of the doors that keep the net catching the fish open while it is being pulled along the seabed. I can just be seen on the far side of the raft. This is a side trawler, that is to say the net is dragged along beside the trawler. The other door will be suspended from aft of the ship, out of this picture. The most common injury we had to deal with is when trawler men caught a particular fish called the 'Weaver Fish', which had poisonous spines. If the spines pierced their hands, their arms would swell up and they suffered fearful agonies with the pain, but they were a stoic bunch and the masters of understatement, to them a slight cut finger would probably mean their arm was hanging off. Like all seamen they were very distrusting of medics. You had to convince them you really did know what you were doing. If you were good your reputation spread, likewise if you were no good, it spread twice as quickly.

Getting aboard a trawler was never an easy task and one had to be a bit of an athlete and chancy with it on occasion. In this picture I am alongside the Hull Trawler 'Faraday' and as you can see the life raft is on the crest of a swell, now is the time to get on the trawler. The large board hanging from the side of the trawler, from what they call the gallows. This is one of the doors that keep the net catching the fish open while it is being pulled along the seabed. I can just be seen on the far side of the raft. This is a side trawler, that is to say the net is dragged along beside the trawler. The other door will be suspended from aft of the ship, out of this picture. The most common injury we had to deal with is when trawler men caught a particular fish called the 'Weaver Fish', which had poisonous spines. If the spines pierced their hands, their arms would swell up and they suffered fearful agonies with the pain, but they were a stoic bunch and the masters of understatement, to them a slight cut finger would probably mean their arm was hanging off. Like all seamen they were very distrusting of medics. You had to convince them you really did know what you were doing. If you were good your reputation spread, likewise if you were no good, it spread twice as quickly.

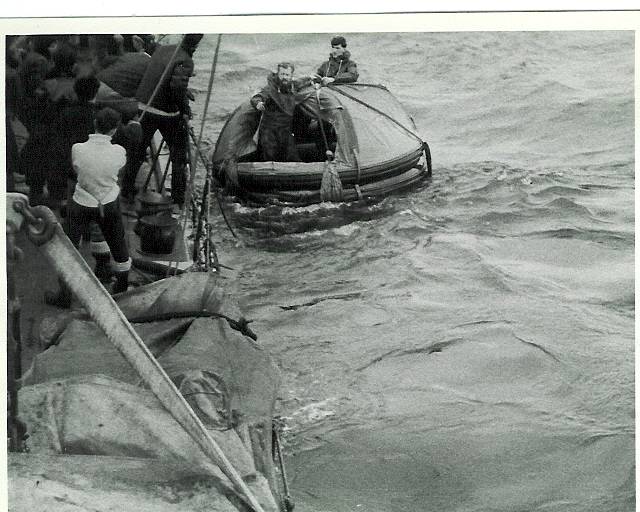

Returning back to the Frigate could be a difficulty as well, particularly if there was more than one in the life raft. The raft was lifted out of the water on a hoist, which was raised by manpower, not by machinery. Therefore one of us had to get out and climb up the scrambling net. Guess who? I have got my leg caught around a nylon line not recovered by one of the seamen. I think the first lieutenant (here securing a line from the raft to stop the sea dragging it away again) whispered a few thoughts to dwell on a little later in the seaman's ear. The weather has deteriorated a little since we started on this particular little jaunt. The ship has to remain stationary while this manoeuvre is carried out otherwise the raft would dip under and fill with water, so everyone gets involved very quickly. No one is excused and much to my amusement, the leading writer who was taking these pictures was very quickly told to stow his camera and get involved on the end of the heaving line. So I am doubly indebted to him. We became great friends.

Returning back to the Frigate could be a difficulty as well, particularly if there was more than one in the life raft. The raft was lifted out of the water on a hoist, which was raised by manpower, not by machinery. Therefore one of us had to get out and climb up the scrambling net. Guess who? I have got my leg caught around a nylon line not recovered by one of the seamen. I think the first lieutenant (here securing a line from the raft to stop the sea dragging it away again) whispered a few thoughts to dwell on a little later in the seaman's ear. The weather has deteriorated a little since we started on this particular little jaunt. The ship has to remain stationary while this manoeuvre is carried out otherwise the raft would dip under and fill with water, so everyone gets involved very quickly. No one is excused and much to my amusement, the leading writer who was taking these pictures was very quickly told to stow his camera and get involved on the end of the heaving line. So I am doubly indebted to him. We became great friends.

There can never be an understanding of what the sea will do. One of the strange experiences I was witness to was during a particularly violent storm. We began receiving odd messages on the ship-to-ship radio. Because of the proximity of whip aerials on board our ship, all radio broadcasts were overpowered by local radio transmissions. If we wanted entertainment we had to prerecord it before we went to sea and play it on closed circuit. On this occasion one trawler was complaining that they had lost a man overboard while they were gutting their catch. They actually said he had jumped ship. They were going to try to search for him. Our skipper was on the

bridge in seconds to organise a search. The next thing we heard was that another trawler half a mile away from the first, started to complain that they had a stowaway on board, and hadn't they got too many mouths to feed as it was? The subject of all this sardonic humour was the deckhand of the first trawler, a man in his fifties who was wearing a fisherman's frock apron; thigh boots and a neckerchief around his neck to stop water getting inside his oilskin. Waves 10 or 15 feet high were sweeping across the decks; he had been lifted by a wave. A pocket of air had been trapped under his oilskin. He was carried over the top of the life line

bridge in seconds to organise a search. The next thing we heard was that another trawler half a mile away from the first, started to complain that they had a stowaway on board, and hadn't they got too many mouths to feed as it was? The subject of all this sardonic humour was the deckhand of the first trawler, a man in his fifties who was wearing a fisherman's frock apron; thigh boots and a neckerchief around his neck to stop water getting inside his oilskin. Waves 10 or 15 feet high were sweeping across the decks; he had been lifted by a wave. A pocket of air had been trapped under his oilskin. He was carried over the top of the life line

rigged three foot above the gunwale and carried on the crest of the wave until he was thrown onto the life boat of the second trawler and impaled by his buttock on the lifeboats anchor blade. There was no possibility that we could do a transfer in that sea, so we had to wait until it calmed. The doctor intended that I should get him from the second trawler, bring him back to Palliser, then we would clean his wound and stitch him up if necessary to finally return him to his own

rigged three foot above the gunwale and carried on the crest of the wave until he was thrown onto the life boat of the second trawler and impaled by his buttock on the lifeboats anchor blade. There was no possibility that we could do a transfer in that sea, so we had to wait until it calmed. The doctor intended that I should get him from the second trawler, bring him back to Palliser, then we would clean his wound and stitch him up if necessary to finally return him to his own

ship afterwards. The ribald humour was fast and furious at the poor chaps expense. The first mate wanted to know where he put his gutting knife before he swam off, among many others not nearly as kind. The pictures are of me getting ready and then going to collect him. Notice how in the pictures above, the first we are going to the rendezvous, in the second we are stopped about to lower the life raft. See how calm the water

ship afterwards. The ribald humour was fast and furious at the poor chaps expense. The first mate wanted to know where he put his gutting knife before he swam off, among many others not nearly as kind. The pictures are of me getting ready and then going to collect him. Notice how in the pictures above, the first we are going to the rendezvous, in the second we are stopped about to lower the life raft. See how calm the water

appears to be in the lee of the weather. The trawler man on the left of the picture beside me is hanging onto a rail. He said he was terrified of being on the warship he felt unsafe and wanted to get back onto his own ship. Bearing in mind what had just recently happened to him on his own ship, I found it very funny.

When we got the man stripped down and inspected the wound in his buttock, it was fairly obvious that we would have to clean him up and take away some dead tissue. He also needed to have the wound stitched up. There wasn't another ship anywhere close to us, so the doctor decided that we would have to do the operation on board, and as he was a bit gung-ho decided it was a good opportunity to exercise the emergency theatre (The Wardroom). He decided that the following morning was the best time, so that we could starve our patient overnight and do the operation in the early forenoon. The poor chap was terrified, and would have been even more terrified if he knew how I felt. The doctor was going to administer the anaesthetic and I was going to have to do the surgery. In essence it was relatively simple, but to me it was monumental. The Supply Officer was going to assist me; the Petty Officer Steward was in charge of sterilising instruments, and preparing the room as a theatre. The whole ships company were agog. The doctor took me to his cabin to explain exactly what he wanted me to do; we thought it a bit unkind to discuss things in front of the poor chap lying in the bottom cot beside us. He was a bit embarrassed when I made him have a good bath; he hadn't had a proper scrub since he left home 10 days or more before. We issued him with new clean clothing from the store and a large brandy when he settled back into bed. So as to make him feel at home, the doctor and I had a glass with him, all down to the Sick bay account of course. He appreciated the meal brought in by the cook himself, 'who said he wanted to see that the condemned man had a hearty supper', then the patient slept like a log until morning. Trawler men work on average 18 hours a day when they are at sea. With only short breaks of about two hours in between shifts, so they are very good at getting to sleep and staying that way until they have to wake up. He was no exception to the rule.

Sick parade was cancelled the next day, those men on treatment reported at 8.o'clock. Sick parade was really a bit of a farce as it was rare to get anyone report in the morning, most injuries occurred during the day or night and were dealt with at the time. Then we closed for business unless it was a really dire emergency. After breakfast the Wardroom was got ready while I got my dressings and instruments sorted the doctor must have rechecked the anaesthetic machine a 100 times. I reckoned if he checked it any more there wouldn't be any gas left in it. I was quite happy with this though, because it showed he was as nervous as I was, possibly because he wasn't over confident in my skills. We got our patient onto the table and having sorted out what we were about, we got stuck in. I gave the doctor a running commentary on what I was doing at my end, while he paid particular attention to his end. The Captain came into the Wardroom to watch what was going on and shouting over the phone to the Pilot, who was Officer of the watch to stop rocking the boat, not an easy thing to do in a ten or twelve foot sea, fortunately there was no wind to speak of so the movement of the ship was pretty steady. I came out of the wound throwing in huge amounts of sulphanilamide powder, until I could eventually sew the edges of the wound together, and put on the final dressings. The patient was resuscitated and the Skipper was handing out glasses of Brandy to the doctor, the Supply Officer and myself. The doctor was on a high and boasting already about the blood and gore. There was very little of either. I was amused to find that the companionways outside the wardroom and sick bay flats were crowded with sailors wanting to know how things went. This was far more interesting than any modern day soaps on television.

The Petty Officer Steward had apparently been giving a verbal report from time to time. He had been watching through the wardroom pantry hatch ready to supply whatever might be needed. He now had to get the wardroom back to normal for the mid day meal. There were plenty of willing hands to carry the patient back to the sick bay and once there I helped him back into bed. Apparently there had been a constant traffic of communication between the trawler fleet and us about the operation while it was in progress. Everyone wanted to know how it was going. The patient recovered remarkably quickly much to our relief. We kept him for a couple of days afterward just to make sure that he had started to heal and there was no sign of any infection, then putting a really firm dressing on we returned him to his own ship, with the necessary notes for his own G.P. I saw him a year later and he reminded me who he was. He told me his G.P. was very impressed with the surgery and the neat scar, which apparently was then very nearly invisible. (My needlework was definitely improving.) I was very pleased to hear it and I must confess a little swollen headed as well.

I think we dealt with just about everything during that month at sea including a trawler skipper from Grimsby who had been 12 weeks ashore while his boat underwent a radical refit. While ashore he had practically lived on Guinness and chips, but as soon as he stepped onto his ship he went dry. That is to say no more alcohol. He started to show symptoms of D.T's (Delirium Tremens) about the time they were off the Faroes. By the time they had reached the Icelandic fishing grounds he was a screaming maniac. The mate had contacted our Captain to authorise him to take over command of the ship and lock up his own skipper for his own safety and that of the crew. Fortunately the mate was qualified within the maritime laws to skipper a boat, and would he hoped soon have his own, so that made it easier. We met up with the Trawler and took the skipper off. It took some time to tempt the man to get into the life raft, but he would only come when we reassured him we already had his wife and concubines waiting for him inside. To describe his conduct and conversation as bizarre would be to put it mildly. He was in a fantasy world all by himself. When we got him to the sick bay and encouraged him to have a wash, he went into a shower with all his clothes and shoes on. He was an incredibly strong man and trying to get him undressed was nigh on impossible. We eventually sobered him up with a bottle and a half of Brandy. He couldn't believe where he was and wanted to know whether he had been shipwrecked. When we explained to him what had happened he was full of remorse. We got him to try to write down what he could remember. He wrote pages and pages of horror, I dread to think what state his mind was in. We fed him up and gradually weaned him off the alcohol sufficient to return him to his ship to let his mate take the ship home for him to see his G.P. When he saw the life raft we had brought him over to us in he was absolutely terrified, and took a lot of convincing to get back in to be taken back to his own ship. I don't know what happened to him afterwards, I would have thought he would not find it easy to get a crew again. That kind of bad news spreads through the fishing fleet like wildfire. The telephone conversations between his own ship and us were open and you can bet the wireless operators would have been listening in to every word and telling their own crews what was going on, it was normal ship-to-ship gossip. The fishing fleet is a very close-knit community, and he would have been very well known in all the fishing ports.

One of the oddities of being in an enclosed ship where you cannot see the outside world for most of the time, you become totally unaware of the movement of the ship and to open a bulkhead door to step out into the fresh air, it comes as a bit of a shock to see the sea horizon at 45 % from what you thought was the horizontal, then to see it move to the same degree on the opposite side. It is only then that you realise it is the ship that is moving at such a roll, not the sea. When we started for home at the end of three weeks patrol I began to unwind. I had to take stock of what we had used to get a shopping list so to speak for replacement. Some men were leaving and their documents had to be up to date. I was losing the doctor and the ship was losing several Officers including the Captain. Between Iceland and The Faroes we went through what must have been a hurricane. The damage to our superstructure was incredible. Both the ships boats (One can just be seen in the photographs above) were stove in, in fact the whaler was gone except for bits of it hanging from the falls. The ships derricks were twisted as if they were made of plastic. The Oerlican gun on the quarterdeck was gone together with all the rest of the furniture and guardrails. I had a locker on the deck above the boiler room, which was plumbed in with steam pipes so that if I had to decontaminate clothing it acted as an autoclave. It was of thick steel construction. It had been stove in as if someone had hit it like a hand chopping a cardboard box. The ship looked as if it had been in a war and just survived. I can honestly say I was completely oblivious of the storm that night which I think was just as well. Our immediate future then was pretty clear. We were going into harbour for quite a hefty repair.

The stares we got from the dockyard maties were quite amusing to see. After having been so long in rough water when I stepped onto the jetty when we finally got alongside I nearly fell over. It is extraordinarily difficult at first to keep balance on a firm ground when you didn't realise the ship had been rolling so much. We made our farewells to men going on draft and prepared to go into dry dock, securing everything that could be removable. I put all the drugs ashore and prepared to go on 2 weeks leave. Before we could go on leave however the Ships Company were put ashore into accommodation at H.M.S Cochrane another so called stone frigate, except the barracks was more like a second world war prison camp with wooden huts for accommodation. The Barracks was on the North side of the Forth near Kirkcaldy in Fife. From there we were bussed into Rosyth each day, and it was to be our home for the next 6 weeks. I had enjoyed my first trip and learnt so much.

The stares we got from the dockyard maties were quite amusing to see. After having been so long in rough water when I stepped onto the jetty when we finally got alongside I nearly fell over. It is extraordinarily difficult at first to keep balance on a firm ground when you didn't realise the ship had been rolling so much. We made our farewells to men going on draft and prepared to go into dry dock, securing everything that could be removable. I put all the drugs ashore and prepared to go on 2 weeks leave. Before we could go on leave however the Ships Company were put ashore into accommodation at H.M.S Cochrane another so called stone frigate, except the barracks was more like a second world war prison camp with wooden huts for accommodation. The Barracks was on the North side of the Forth near Kirkcaldy in Fife. From there we were bussed into Rosyth each day, and it was to be our home for the next 6 weeks. I had enjoyed my first trip and learnt so much.

Leave was pretty uneventful, I spent most of my time doing domestic chores or cycling around London following the brass band concerts in the parks. Friday evenings would be spent at the dancing club in Strutton Ground, so when it came time to return to Rosyth I was not sorry to return. On my return the ship looked a sorry sight in dry dock with scaffolding all over it and Dockyard workers seeming to occupy every part of the ship. I was able to get the Sick Bay painted from a ghastly dark yellow and brown into white with a bright blue trim. The desk and cupboards were ripped out and fitted units put in their stead. A new deck covering of a blue composition that matched the colour on the bulkheads made it look more like a Sick Bay than a sanitary unit.

New crewmembers were joining all the time and I had to make sure that they were up to date medically and dentally. It isn't a good idea for someone to go down with a raging toothache three days at sea, because he would have to live with it for a month or chance my ministrations. Some might have considered suffering for a month as the lesser of the two evils.

There were a lot of incidents occurring the whole time we were in Rosyth and sailors meeting with various apparitions ashore disguised as innocent maidens resulted in a few of them reporting sick the next day with venereal problems. All grist to the mill in the average Sick Bay, hence the skill of the average Sickbay man in taking, staining and reading clinical slides. One of the most amusing incidents involved one of the Dockyard workers who we suspected was a communist and we were told a Trade Union rep'. He was the most unpleasant and lazy one on the ship, and completely objectionable. He was also suspected of taking some tools belonging to tradesmen on the ship like Electricians. After a month of his totally obstructive and insulting behaviour, at 4.p.m one afternoon the Bosun informed him that there was a telephone message for him at his works office. He promptly locked his tool kit up and threatened dire consequences if anyone moved it. As soon as he was on the dockside heading toward his office, one of the seamen had picked the lock on his toolkit, taken out all the contents and nailed the metal box to the work bench then replaced all the tools minus those which were obviously stolen because they were marked with the stamp of the Electrician who had lost them. These were returned to him. Other Dockyard employees who obviously didn't like the chap either saw all this. The lock was replaced and things looked exactly as they were before. The Dockyard man returned after 1/2 an hour and just sat by his toolbox moaning because there wasn't a call for him at all, it was for someone else. He opened his box to pretend he was busy but at 5 o'clock he had the lock on his box quickly; he was always the first off the ship at night. He grabbed the handle of his box and started to run but his arm was nearly pulled out of its socket when his toolbox didn't budge. He tugged and tugged and eventually had to empty the toolbox to discover what was wrong. Blasphemy and curses in a rich Scots accent are not usually pleasant to hear, but everyone was in hysterics. No one knew however who had done the deed! And to make matters worse the Dockyard Police stopped and searched him because he was so late going out, they suspected he might be trying to smuggle something out. He was apparently purple with rage when they let him go. He got himself transferred to another job on another ship the next day. Surprisingly, afterwards the rest of the Dockyard employees were great fun, and worked twice as hard without his presence to subdue them, we kept them supplied with the duty free cigarettes, (The ration went up to 600 a month at sea) it was surprising how many extra jobs got done that were not on the job sheets. It turned out he was as unpopular with them as with us.

It was at this time while ashore at a dance in Dunfermline that I met a girl called Annette. We got on extremely well although she couldn't dance. She was a student nurse at the local hospital. She took me home to her home in Leven, which is further along the north coast of the Forth from Kirkcaldy. We got on very well indeed together so much so that we eventually agreed to get married. I respected her very much and although there was opportunity enough we never ever went beyond the bounds of propriety. I was a little bit surprised and annoyed when twelve months later she opted out of nursing training and went to Finland as an Au Pair. She wrote regularly to me but she was there for 12 months and I couldn't understand why she went there in the first place. I was still expected to visit her home, which I did from time to time. I didn't see much of her when she returned and learnt later that she had called on my mother in tears to tell my mother she had got herself pregnant. It was much later that I found this out, but the relationship just stopped without explanation. This was the third time that I had respected a girl and they had been playing with someone else and I was becoming very sceptical of women in general. I was so disgusted with her, I really expected better.

In the meantime the ship was ready for sea, and it was a great relief to move out of Cochrane and back on board. I was moved to mess midships in the electricians' mess. This was obviously more convenient for a whole host of reasons, being convenient for the Sickbay being one of the obvious ones. Not having to clamber up from the after mess in really inclement weather to get to the Sickbay in rain or snow was another, particularly when the main deck was awash. We had a new Captain, Lieutenant Commander the Right Honourable John Fremantle, and a new Doctor, Surgeon Lieutenant Eastwood. A Gynaecologist by specialisation, not a lot of use in a completely male society, we certainly weren't going to come across very many pregnant trawler men, but there could always be a first I suppose. He was fresh faced and very much a mummy's boy. He started to save up his socks in the sick bay to take home for mother to wash, until I respectfully explained to him where he could keep his dirty laundry. Clinically he was excellent, but he was completely out of his proper environment, and a little intimidated by

some of the harder crewmembers; un-necessarily so because at heart they were as soft as putty and would do anything for anybody. They were in general excellent tough seaman. He was also terrified of the First Lieutenant who insisted that he would be using the bottom bunk in the sick bay to sleep in. I soon fixed that nonsense when one of the coarsest seamen on board went sick with a common cold, I had him hospitalised in the Sickbay for a couple of nights, to prevent him infecting the rest of the men on his mess deck. The Jimmy (1st Lieutenant) was not amused, and soon went back to his own cabin. It took me a long time to get in the Jimmies good books again, but I had the Captain on my side, and besides I liked to sleep in the Sick Bay, I could be found a lot quicker there. In fact that is where they always came first to find me, or called me on the ships telephone. There was the odd occasion when a telephone call from the Captain was more discreet than to have me piped to his cabin by the Bosun.

some of the harder crewmembers; un-necessarily so because at heart they were as soft as putty and would do anything for anybody. They were in general excellent tough seaman. He was also terrified of the First Lieutenant who insisted that he would be using the bottom bunk in the sick bay to sleep in. I soon fixed that nonsense when one of the coarsest seamen on board went sick with a common cold, I had him hospitalised in the Sickbay for a couple of nights, to prevent him infecting the rest of the men on his mess deck. The Jimmy (1st Lieutenant) was not amused, and soon went back to his own cabin. It took me a long time to get in the Jimmies good books again, but I had the Captain on my side, and besides I liked to sleep in the Sick Bay, I could be found a lot quicker there. In fact that is where they always came first to find me, or called me on the ships telephone. There was the odd occasion when a telephone call from the Captain was more discreet than to have me piped to his cabin by the Bosun.

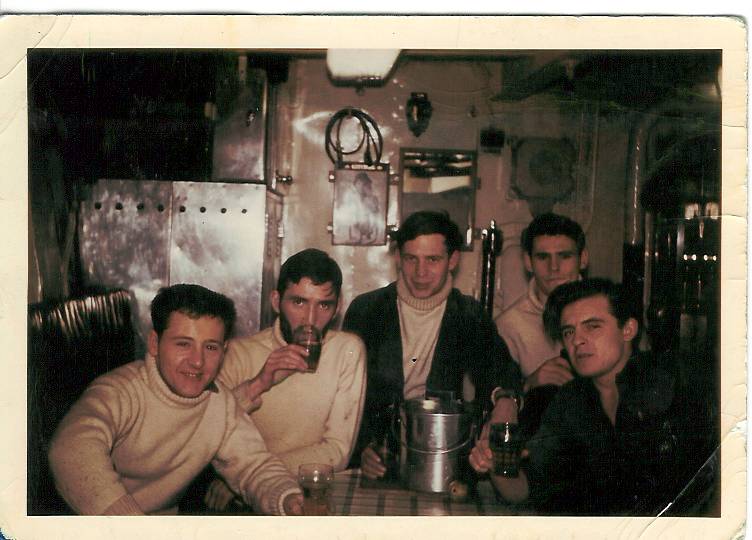

The 1st Lieutenant was the same as before, which was a relief as he was familiar with the routine for transferring at sea with the Life raft, and very quickly had the routine in motion again when it was needed. We sailed from Rosyth in fine weather and the trip out for the first couple of days was idyllic. I had little or no work to do apart from cleaning the Sick bay during the forenoon, until Tot time and in the afternoon reading or getting on with a Tapestry I had bought during the refit. This was something I could work on and stow away very quickly if necessary. I still have the finished Tapestry as a fire screen; it took me almost the next 18 months to complete. A surprising number of the crew became seasick on our way out, not least among them was the doctor who took to his bed and certainly looked a very pale shade of grey. It was a source of great amusement to the crew that my first patient was the doctor. I felt a bit sorry for him really because I don't think he was getting a lot of sympathy in the ward room either. When he recovered sufficient to come into the sick bay I couldn't convince him to use one of Dr Campbell's' diagnosis which was simply O.P (i.e. Oscillating Plumbi) I then had to give out a placebo which was to be taken immediately before turning in; this comprised a coloured tablet which was chalk with a sugar coat and No, they were not excused their watch or put on light duties. He always insisted on doing a thorough check on each man, I had to put up with it but he soon learned that some men were using this kind of treatment as a way of skiving off work. I think he was got at by the 1st Lieutenant again about this. It was a pity because he was out of his environment completely; he was a clinician not a man to deal with the likes of these sailors and their often-spurious problems. My extramural duties included showing films on various mess decks in the evening with a 16 m.m. film projector, (all film shows had to include a Tom an Jerry or there would have been a mutiny), or treasurer for the Tombola games. This I enjoyed because I could not play, but it was expected that the winner would put a percentage of his winnings into a kitty for the committee, the caller, a referee and myself. The largesse depended on how much was won, or how much beer the winner had drunk. By law, all the money taken had to be handed out to the winners of the game. It really was a good money earner for me. The nature of my job seemed to imply that I would not fiddle the takings, and I was completely trustworthy! I didn't need to draw on any of my pay during this time. The caller was the Chief Petty Officer Stoker, and the referee was a Petty Officer Seaman Gunner. My closest friends on board at that time were the Leading Writer and a Seaman (Peddler Palmer) whose birthday was on the same day as mine.

We weren't long on station before the emergency calls started coming in. the first one we received the doctor decided he was going to transfer with me, I found him an immersion suit and he was obviously looking forward to the job until he saw the Life raft hanging over the side of the ship. I think he thought he was going to get into it and be hoisted over the side. The poor chap was in a terrible situation with all the grinning seamen watching to see what he was going to do. I climbed into the raft with the kit and at the first opportunity the 1st Lieutenant said "o.k. Doc", I grabbed hold of his wrist and he was in. I managed to keep him upright so he didn't look as if he had been pulled in. He looked a little shaken, but he turned to me and said thank you, which he really meant. I explained to him that on the other side when I told him to go, he would grab the gunwale and pull himself over and I would be giving him an unceremonious shove from behind. The trawler men would almost certainly grab him and pull him inboard so he had nothing to worry about. He wasn't to wait for me but to get clear, then I would come after him after I had the life raft secure. He dealt with the casualty very well, and we returned to Palliser relieved with his first ordeal. He really didn't enjoy the trip because one of the difficulties was that if you were inclined to be sea sick the life raft would certainly remind you of it because you could feel every ripple of the waves beneath your feet, and the raft moved over every crest and into every dip in the waves. Once back on board he had to report to the Captain and then he was back in his cabin. I got the Officers Steward to take him a strong cup of tea in his cabin. After that he declined to go across again unless it was really urgent, leaving me to do most of the transfers solo.

Some of the transfers

like this one to S.T. Grimsby Town were simple and others were definitely not. In this illustration under almost windless conditions in high summer this transfer is by heaving line and carried out without any bother at all. The cod end of the fishing net can be seen hanging from the boom on the far side of the ship, and the lines attached to the raft can clearly be seen on the right of the picture. In the next picture things are a little different as there was a wind with a sea running and the trawler tended to wallow one minute and roll away the next which meant I had to pick my moment to climb aboard. But it wasn't all bad news, we had a very good rapport with the fishermen and on every occasion I transferred across, they would throw a couple of baskets of fresh fish into the life raft straight off the deck ready gutted for us. This included Cod, Skate and Sole in fact almost anything. On one occasion I crossed over to what is referred to as a liner. This is a fishing boat which does not use a net, but pays out a number of lines each one baited at every so often along its length. The lines can be miles in length and are dragged

like this one to S.T. Grimsby Town were simple and others were definitely not. In this illustration under almost windless conditions in high summer this transfer is by heaving line and carried out without any bother at all. The cod end of the fishing net can be seen hanging from the boom on the far side of the ship, and the lines attached to the raft can clearly be seen on the right of the picture. In the next picture things are a little different as there was a wind with a sea running and the trawler tended to wallow one minute and roll away the next which meant I had to pick my moment to climb aboard. But it wasn't all bad news, we had a very good rapport with the fishermen and on every occasion I transferred across, they would throw a couple of baskets of fresh fish into the life raft straight off the deck ready gutted for us. This included Cod, Skate and Sole in fact almost anything. On one occasion I crossed over to what is referred to as a liner. This is a fishing boat which does not use a net, but pays out a number of lines each one baited at every so often along its length. The lines can be miles in length and are dragged

along the seabed to catch the larger fish that live there. When I returned to Palliser on that occasion they only gave me one fish. A flounder. This time I had to pose with the one that didn't get away and I have won many a pint on the strength of it. This is the fisher mans' catch to beat all comers. The original picture is a bit dog-eared now having been obliged to show it to prove my yarn. There were more hazardous occasions, possibly

along the seabed to catch the larger fish that live there. When I returned to Palliser on that occasion they only gave me one fish. A flounder. This time I had to pose with the one that didn't get away and I have won many a pint on the strength of it. This is the fisher mans' catch to beat all comers. The original picture is a bit dog-eared now having been obliged to show it to prove my yarn. There were more hazardous occasions, possibly

the worst being when I was returning from a visit to a trawler when the weather deteriorated rather rapidly. I had gone over on a free drift and had spent a little longer than anticipated. I had already been warned by the Captain to try to get a wriggle on and I was as quick as I could be. Palliser had stood well off as the wind was getting up. I got into the life raft and the trawler pulled away as quickly as it could. By this time Palliser was half a mile or more away and the sea was building up alarmingly. It was a case of now I see you, now I don't. Gradually I saw it approach me getting closer as I rose on every wave top it got really close barely moving now, I saw that there was a line of seamen along the ship each of them swinging heaving lines ready to throw to me. One man was right in the bow, getting soaked every time the ship dipped into the next wave. The ships bow came within inches of me as I was concentrating on trying to get hold of the first line that was thrown. I missed the first but caught the second, but I was slowly drifting away from the ship. One minute I was looking up at the bottom of the ship the next I was high on a crest looking down on the bridge. I had caught a line and was holding on like grim death. There was a struggle on the ship to pass the line astern to the waist by the crane, without losing hold of it. When I was level with the waist and the sailors had got their end of the heaving line back to the waist I was about fifteen or twenty feet away and the line was taut. The seaman had put a turn around a cleat on the deck and I put a knot with the other end through the ring on top of the life raft lashings. My hands were frozen and I had difficulty trying to hold it. Normally there was a seaman holding a telephone from the waist to the bridge to relay the 1st lieutenants instructions to the bridge, because the Captain cannot see what is happening in the waist, from the bridge. When I had taken hold of the line, the Captain had stopped engines, so the ship was wallowing in a heavy sea. Not a very good idea, so he wanted to get under way again. The 1st lieutenant made a junior seaman take the telephone to get the stronger man onto the hoist, with the line between the life raft and the ship taut, the captain had asked the telephone number whether the life raft was secure, he had said yes, so the Captain ordered the ship slow ahead. The result was that the ship went forward and the life raft was dragged alongside with the line attaching the raft to the ship so taut it couldn't be loosened. The stern of the ship lifted clean out of the water on a wave and the life raft swung underneath. I couldn't fend off, so as the stern came down onto the life raft it collapsed in on me. I don't know how far down I went, but the rubber seals on the neck and sleeves of my immersion suit split and my suit filled with freezing water. Surprisingly I felt very calm and amazed to see what a beautiful emerald green the sea was; and I actually saw the propeller just moving by my right. There was apparently a rush situation on the deck above me. A pipe had been made for all available hands to go to the waist and help lift the raft, as the ship lifted again the raft popped out with me still trapped under the collapsed canopy. As daylight appeared I felt a weight drop onto my back. What had happened was a sailor had jumped from the ship with the hook in his hand onto the top of me as I came up. He had immediately hooked onto the ring and held it tight and ready to fend off from the ship if there was any danger of going under again. The slack was taken in with lots of shouts on the deck and slowly we were lifted out of the sea. When I was swung onto the deck I was amazed to see so many men on the heaving line including another Officer, a cook, and a stoker who had rushed up from the engine room and the leading writer had come from his office. They were all soaked as well because waves were rolling along the deck. I was dragged out of the raft and rushed forward to the sick bay by two petty officers who then helped me out of my immersion suit. My hands were too numb, and in truth I felt like crying as they thawed out. I was a little bit annoyed that the doctor never came near me until the next morning, and then never made any mention of what had happened on the transfer, I don't believe he didn't know because it was the talk of the ship and Officers don't usually clear deck to get on the end of a heaving line. I went into the sick bay and stripping completely went into a shower to thaw out and freshen up. I had missed the tot at lunchtime but when I came out of the shower the 1st Lieutenant was in the sick bay with a double tot of neat rum for me. He apologised for my soaking, but I really don't think anyone was to blame. I had taken so many chances with the sea I suppose it was about time I was taut a lesson.

the worst being when I was returning from a visit to a trawler when the weather deteriorated rather rapidly. I had gone over on a free drift and had spent a little longer than anticipated. I had already been warned by the Captain to try to get a wriggle on and I was as quick as I could be. Palliser had stood well off as the wind was getting up. I got into the life raft and the trawler pulled away as quickly as it could. By this time Palliser was half a mile or more away and the sea was building up alarmingly. It was a case of now I see you, now I don't. Gradually I saw it approach me getting closer as I rose on every wave top it got really close barely moving now, I saw that there was a line of seamen along the ship each of them swinging heaving lines ready to throw to me. One man was right in the bow, getting soaked every time the ship dipped into the next wave. The ships bow came within inches of me as I was concentrating on trying to get hold of the first line that was thrown. I missed the first but caught the second, but I was slowly drifting away from the ship. One minute I was looking up at the bottom of the ship the next I was high on a crest looking down on the bridge. I had caught a line and was holding on like grim death. There was a struggle on the ship to pass the line astern to the waist by the crane, without losing hold of it. When I was level with the waist and the sailors had got their end of the heaving line back to the waist I was about fifteen or twenty feet away and the line was taut. The seaman had put a turn around a cleat on the deck and I put a knot with the other end through the ring on top of the life raft lashings. My hands were frozen and I had difficulty trying to hold it. Normally there was a seaman holding a telephone from the waist to the bridge to relay the 1st lieutenants instructions to the bridge, because the Captain cannot see what is happening in the waist, from the bridge. When I had taken hold of the line, the Captain had stopped engines, so the ship was wallowing in a heavy sea. Not a very good idea, so he wanted to get under way again. The 1st lieutenant made a junior seaman take the telephone to get the stronger man onto the hoist, with the line between the life raft and the ship taut, the captain had asked the telephone number whether the life raft was secure, he had said yes, so the Captain ordered the ship slow ahead. The result was that the ship went forward and the life raft was dragged alongside with the line attaching the raft to the ship so taut it couldn't be loosened. The stern of the ship lifted clean out of the water on a wave and the life raft swung underneath. I couldn't fend off, so as the stern came down onto the life raft it collapsed in on me. I don't know how far down I went, but the rubber seals on the neck and sleeves of my immersion suit split and my suit filled with freezing water. Surprisingly I felt very calm and amazed to see what a beautiful emerald green the sea was; and I actually saw the propeller just moving by my right. There was apparently a rush situation on the deck above me. A pipe had been made for all available hands to go to the waist and help lift the raft, as the ship lifted again the raft popped out with me still trapped under the collapsed canopy. As daylight appeared I felt a weight drop onto my back. What had happened was a sailor had jumped from the ship with the hook in his hand onto the top of me as I came up. He had immediately hooked onto the ring and held it tight and ready to fend off from the ship if there was any danger of going under again. The slack was taken in with lots of shouts on the deck and slowly we were lifted out of the sea. When I was swung onto the deck I was amazed to see so many men on the heaving line including another Officer, a cook, and a stoker who had rushed up from the engine room and the leading writer had come from his office. They were all soaked as well because waves were rolling along the deck. I was dragged out of the raft and rushed forward to the sick bay by two petty officers who then helped me out of my immersion suit. My hands were too numb, and in truth I felt like crying as they thawed out. I was a little bit annoyed that the doctor never came near me until the next morning, and then never made any mention of what had happened on the transfer, I don't believe he didn't know because it was the talk of the ship and Officers don't usually clear deck to get on the end of a heaving line. I went into the sick bay and stripping completely went into a shower to thaw out and freshen up. I had missed the tot at lunchtime but when I came out of the shower the 1st Lieutenant was in the sick bay with a double tot of neat rum for me. He apologised for my soaking, but I really don't think anyone was to blame. I had taken so many chances with the sea I suppose it was about time I was taut a lesson.

There were so many incidents that this isn't really the place to tell the stories, but two I will recount. I was transferred to a Belgian trawler; the sea was too heavy for a line transfer so I had gone over on a free drift. When I climbed onto the trawler the crew had the deck alive with their catch, which they were gutting. I noticed that all the crew were in oilskins and sea boots except one man who was in a shirt and jeans and wearing wooden clogs. With water surging onto the deck and out again through the scuppers, I asked the skipper why that man wasn't dressed for the weather. He told me that the man was from a prison in Belgium. He had created trouble in the prison, and a magistrate had sentenced him to four weeks on a fishing trawler. He had been brought to the trawler the day the ship sailed and his escort left him when they were about a mile at sea. He had to work like all the other deck hands until they returned, but he only had the clothes he stood up in. when he returned he would be met and taken back to prison to finish his sentence. The skipper said it was unknown for a prisoner to go to sea twice!

The second incident involved a Dutch trawler. The doctor came with me on this occasion, and again it was a free drift. After we had treated the sailor for a wound, which had become infected, the doctor wanted to see the man again in a week. At the time we were in a haven off the northwest corner of Iceland. I talked ship to ship with the Captain to make the arrangements and he wanted to be of an island called Ingelshofti, (The spelling may be a bit amiss, but it means 'Horses Hoof' and seen from the sea that's what the island looks like). I knew where it was and tried to explain to the skipper. I asked to show him on a chart, but he showed me his chart cupboard and he didn't have a chart on the ship. He explained it had been his fathers ship, and he thought his father may have kept some charts but he never bothered. He was going fishing off the rich Greenland ground under the ice cap. I drew a rough diagram of where I wanted to meet him again at 4.p.m on the following Sunday. (7 Days away) we left and waited. We moved around eventually to the new station and on the Sunday following at 4.p.m. precisely we saw the Dutch trawler appear over the horizon. I couldn't believe anyone could be so clever.

In the two years I was on the Palliser we paid two visits to a foreign port. The first was to Goteborg in Sweden. We spent a week there simply enjoying a foreign holiday. The second, a year later was at a small town called Odda at the top of the Hardanger Fjord in Norway. Of the two places, I liked Norway the best. In Sweden we were moored in the harbour and had to rely on the liberty boats to take us ashore. In Norway we were tied up against the harbour wall in the middle of the town. We were particularly popular with the young people, because the beer is so expensive there, we took our own ashore and shared it; in Norway it could only be bought with a meal with a limit of only two bottles per person.

The only other change from our routine in the Fishery protection was a trip to Belfast in Northern Ireland where the Home Fleet had gathered for exercises in the North Atlantic. This comprised a few days chasing each other and us trying to find Submarines with our Sonar. It was all very friendly schoolboy adventure stuff with no real chance of anybody being hurt or sunk. Everyone on board entered into the spirit of the games, me included. We had lost our doctor temporarily because he was only required to be on board while we were off Iceland. Therefore, for what I was worth, I was the only medical support on board, and this was when I won the 1st Lieutenants heart again. The 1st Lieutenant had been a bit harsh with the seamen over the training exercises, and they were not happy. When the klaxons went off to send everyone to battle stations one day, I went to the sick bay which was my battle station and having checked my valise and knowing my department was all in order, I settled down to get on with my tapestry. I had closed the dead lights, (metal covers which dropped down over the portholes) I couldn't see out so just sitting there waiting for a call I knew wasn't going to come I might just as well do something useful. On this particular occasion, I had just got the tapestry bag out of the cupboard when the phone rang and I was called to the bridge immediately. I ran up with my valise. The hatch to the bridge was open for me and when I got there, the rather irate Captain told me to see what I could do with the 1st Lieutenant. There was a lot of activity going on as we were apparently under attack from two submarines and he didn't want to be distracted. The 1st Lieutenant was sitting in the Captains chair pasty faced obviously in shock. What had happened was that as he was climbing through the hatch to the bridge a seaman had dropped the hatch cover too early catching the 1st lieutenants leg just below the knee and because he was moving so quickly had dragged his leg clear of the hatch de-gloving the flesh from his shin from the knee to his ankle. The tissue was rolled up on the top of his sock and boot. I pulled up his trouser leg to his knee and unrolled the tissue and put it backing place to bind it up firmly. Surprisingly he had lost very little blood. I wanted to get him laid down in the sick bay with his leg elevated, but I was over ruled and he insisted that he stay at his post. I told him that the wound would have to be stitched up or else he would have real problems afterwards. The Captain said I could do it after the exercise was over. The 1st Lieutenant called around the entire fleet to get a doctor to transfer to sew him up, but as the doctors were too concerned in staying on their own ships and they knew there was a Sickbay man on board, they said that I should do the job. After the morning exercise was completed and the crew stood down from action stations 'Up spirits' was piped and almost a second after I was told over the tannoy to stay in the Sick bay to wait for the 1st Lieutenant. I was already waiting for him anyway with my steriliser going. He came in looking very grey and apprehensive, but I got him to relax and sat him in a chair with his leg high. I gave him the option of a local anaesthetic, but suggested that in the long run it would be less painful without and he could move around a bit quicker. He opted for no anaesthetic. I made him as comfortable as I could and gave him a magazine to read and ignore me. It took me a little while to clean the wound and it was beginning to hurt him. I talked to him the whole time and explained what I was doing and why. When I had finished I think there were about 20 or 30 stitches all told, I bandaged him up and gave him an injection of penicillin, then I took him to his cabin and got him to lie down. I saw the P.O. Steward and told him to take the Jimmy his lunch to his cabin and a stiff one of his favourite drinks. Then went to my own mess for my own tot of rum. I went down to see the Jimmy a couple of hours later and gave him a sleeping tablet and a pain killer then reported to the captain to tell him what I had done. He was excused his watch that evening and a message was sent to him to that effect. At five o'clock that evening I was called to the sick bay to find the 1st lieutenant waiting for me. I checked his dressing and decided to leave it well alone for a few days. His temperature was normal and there was no heat around the bandage. When he left he gave me a small brandy bottle that contained neat rum and said he hoped he didn't find me saving my tot when he did rounds the next time. He need not have worried the bottle is still somewhere at the bottom of the sea outside Belfast.When I looked at the wound the next time it was healing beautifully, and not long after the stitches were taken out the scar was barely visible. He made a point of showing it to the doctor when he rejoined us; the doctor was very impressed.

Of all the transfers I took part in, and there were 179 separate incidents in all. The most dramatic occurred on the morning of the 8th July 1960. I was woken up by a messenger from the bridge at 5.a.m. and asked to go to the wireless room to speak to a trawler skipper. I went at once and there was a conversation going on with the Officer of the watch. I cut in and introduced myself. The skipper told me that they had a man in the waist of the ship and they couldn't rouse him. I asked, was he able to respond at all? But the skipper didn't think so. Could anyone find a pulse, in his neck maybe? They weren't sure. To the Officer of the watch, are we anywhere near? About half an hour away! Can we arrange a transfer please? The trawler skipper cut in, he would like that very much. Are there any other problems, we are hauling up our nets we will meet you. I went on up to the bridge and told the Officer of the watch I was not happy with the skippers reply, I thought it was evasive. He told me to get ready to transfer; the Captain and 1st Lieutenant were being informed now. I requested that the doctor be asked to transfer as well. The galley was not open this early so there was no tea available, I went straight to the sick bay and got ready. The doctor came in still in his dressing gown, he didn't look very happy but when I explained to him what had occurred he agreed to get ready to transfer with me. It was light already despite the early hour, but there was a thick sea fog. There was no wind and the sea was running a four or five foot swell. It was decided that we would do a line transfer. Men were running around to wake all those required to help with the life raft as we headed toward the Trawler. It wasn't long before almost the entire ships company were awake, because of the activity everyone knew something unusual was happening. I went up to the bridge when I was ready and waited by the riflemen with their line, ready to fire it over the trawler so we could be pulled across. The Captain asked me what I thought was the matter, and I told him that I feared the worst but hoped I was wrong. I didn't think the skipper was telling us the whole truth. Moments later the trawler appeared out of the mist over

on our port bow and then we saw the smoke pouring out of the space immediately behind the bridge house. The ship was on fire. There was a panic as orders were shouted for a couple of seamen and a Petty Officer to get ready to transfer with all available fire fighting equipment they could carry. The trawler stopped while we got into position, I think the doctor became a frightened man at that stage. I had a couple of oxygen cylinders with me together with mask etc to resuscitate the man if necessary, not altogether a good idea to use these near a fire, but I still didn't know what we were going to have to deal with. We got away in the life raft as quickly as we could but made heavy weather of getting over to the trawler with so many men and so much weight in it. I was the first onto the trawler leaving the doctor to his own devices. The man was lying on the deck in the waist as the skipper had nearly informed us. The sea was slopping in and out of the scuppers washing over him every time the ship rolled. He was blue and I could not find a pulse he was definitely not breathing. I gave him a stimulant by injection and a whiff of Oxygen, but it was obviously futile, he had been dead a short while, but the crew who were watching me at least saw that we tried something, so it was as much for their benefit as the patients. I asked the doctor if he would declare him dead and issue a death certificate but he wouldn't even get down and go through the motions, he just stood there staring. I suggested he should go and talk to the Skipper on the bridge. I found the First Mate and actually grabbed his arm to stop him charging about. I told him I wanted the dead man moved off the deck and were there any other men missing? He said he didn't know. So I told him to find out sharp. He did a quick check and said there were 4 unaccounted for.

on our port bow and then we saw the smoke pouring out of the space immediately behind the bridge house. The ship was on fire. There was a panic as orders were shouted for a couple of seamen and a Petty Officer to get ready to transfer with all available fire fighting equipment they could carry. The trawler stopped while we got into position, I think the doctor became a frightened man at that stage. I had a couple of oxygen cylinders with me together with mask etc to resuscitate the man if necessary, not altogether a good idea to use these near a fire, but I still didn't know what we were going to have to deal with. We got away in the life raft as quickly as we could but made heavy weather of getting over to the trawler with so many men and so much weight in it. I was the first onto the trawler leaving the doctor to his own devices. The man was lying on the deck in the waist as the skipper had nearly informed us. The sea was slopping in and out of the scuppers washing over him every time the ship rolled. He was blue and I could not find a pulse he was definitely not breathing. I gave him a stimulant by injection and a whiff of Oxygen, but it was obviously futile, he had been dead a short while, but the crew who were watching me at least saw that we tried something, so it was as much for their benefit as the patients. I asked the doctor if he would declare him dead and issue a death certificate but he wouldn't even get down and go through the motions, he just stood there staring. I suggested he should go and talk to the Skipper on the bridge. I found the First Mate and actually grabbed his arm to stop him charging about. I told him I wanted the dead man moved off the deck and were there any other men missing? He said he didn't know. So I told him to find out sharp. He did a quick check and said there were 4 unaccounted for.

The Petty Officer and a Leading seaman from Palliser had begun to get the fire under control; the smoke was coming from the passageway, below a vertical hatch, where the senior crew had their cabins. I told the P.O. that there were four men missing, and said I would try to go down and see if I could find any if he would keep the hose turned on me. I went down the hatch and got onto my knees and started to crawl along the passage. I couldn't have gone far when I found the first man. I don't know how I picked him up, but I got him across my shoulders and got back to the foot of the ladder. I must have got half way up the ladder when he was lifted bodily off my shoulders and I practically flew up the last few rungs. He was not breathing and covered in burns from the waist up. I gave him a full blast of oxygen and he started to cough and breathe again. I got him into the main cabin below the bridge which was the deck hands sleeping quarters. I had him laid down a called the doctor down off the bridge and told him we had another casualty. Then the mate came up with another, then the Petty Officer and lastly the Leading Seaman with the fourth. None of them were breathing but they all, thank goodness, started again after I had force-fed them oxygen. They were all suffering severe burns and shock, as well as smoke inhalation. The doctor was looking as shocked as they were, but he did manage to give them each a large dose of penicillin. One man (A Mr Willets) had suffered a scorch mark across the white's of his eyes while he was unconscious I suspect, the only eye drops I had with me were 'Albucid', which I put onto his eyes. It made him weep but it was the only thing I had to keep his eyes lubricated, in an attempt to stop them scarring. I had two sachets of intravenous saline and I was able to put drips up for two of the men, I had to splint the arms of one of them and tie him down to his bunk because he was semi comatose and very restless. I gave them all morphine, and arranged to transfer back to Palliser to get more equipment. I had to give the Captain an account of what had happened, the fire was now out, the nets were inboard, ideally I would like to have all the injured men on Palliser, but I thought the transfer could kill a couple of them. I was to return to Palliser to get my supplies, and then travel back on the trawler to Grimsby. The skipper would not go into Iceland because there was a warrant there for him and his ship. He would lose his ship and all his gear and be fined a huge sum of money. Either way we had to take the dead man back to Grimsby for the Coroner.

I returned to Palliser, and after a mad chase around collected all my kit together, every man on board going out of his way to help me. I completely forgot all about my own personal kit. Eventually I was ready to return and was taken back this time with the Engineer Officer who was going to assess the damage and safety of the trawler, and try to establish how it started. (It was apparently caused by a smouldering cigarette in an armchair that got re-ignited by a draft as the trawler turned to draw in its catch.) When I returned I set up drips for the other two men and dressed all their burns with Vaseline gauze. I started to re-lubricate Mr Willets eyes every two hours and kept watch on all the drips, I changed them all once and hoped that I had given them enough to relieve their shock, but they were all quivering and in a lot of discomfort and pain. The dead man was the cook, so one of the deck handstook his place.

The life raft returned to the Palliser with the Engineer Officer, and the Doctor, leaving a stoker and a seaman to help the crew and replace the injured men. We immediately started for Grimsby leaving Palliser behind. I was not really aware of when we started, I only felt the change in the movement of the ship, which was somehow unlike the Palliser, it was much more like a rolling motion, but not unpleasant. The new cook came and asked me if I would like a drink of tea, I said I would and what time was it. He told me it was 4 o'clock. That was my first cup of tea that day, all of a sudden I felt hungry. I stayed with the patients all the time except when I got a man to relieve me when I went for a meal. They were improving the whole time and more responsive to me, but kept my eye on the shock, I gave them a booster of penicillin later in the evening and I gave a booster of morphine to two of them, but that was going to be their last. I got them to eat and drink. I was moderately satisfied with the progress of two of them, but the others gave me some concern, I was most concerned about Mr Willets' eyes. About two a.m. I asked the skipper if he could raise the hospital in Faeroe. I knew there was a hospital at Torshavn on the north island. We made contact and through the embassies, the skipper gave an E.T.A. of 8.a.m. we arrived alongside dead on the dot of 8 a.m. he made his calculation by simply looking out of the window of his bridge, asking the helmsman what was the bearing and speed, thought for a moment and stated the time. I don't think these men would ever need satellite navigation systems.